Bereaved Paths: Navigating Burial Dilemmas and Identity Shifts in Ultra-Orthodox Society

Fourteen former members of the ultra-Orthodox community had died in the war in Gaza, and five more were killed at the party on Kibbutz Re’em on October 7. From the moment that they receive the tragic news, families of these soldiers must deal not only with their grief but also with painful decisions about the burial and commemoration of their fallen loved ones – dilemmas that cut to the very core of the crossroads that ultra-Orthodox society finds itself about Israeliness as a whole. Shomrim presents the stories of three such families.

Fourteen former members of the ultra-Orthodox community had died in the war in Gaza, and five more were killed at the party on Kibbutz Re’em on October 7. From the moment that they receive the tragic news, families of these soldiers must deal not only with their grief but also with painful decisions about the burial and commemoration of their fallen loved ones – dilemmas that cut to the very core of the crossroads that ultra-Orthodox society finds itself about Israeliness as a whole. Shomrim presents the stories of three such families.

Fourteen former members of the ultra-Orthodox community had died in the war in Gaza, and five more were killed at the party on Kibbutz Re’em on October 7. From the moment that they receive the tragic news, families of these soldiers must deal not only with their grief but also with painful decisions about the burial and commemoration of their fallen loved ones – dilemmas that cut to the very core of the crossroads that ultra-Orthodox society finds itself about Israeliness as a whole. Shomrim presents the stories of three such families.

An ultra-orthodox man on the Gaza border last November. Photo: Reuters

Ayelet Kroizer

January 15, 2024

Summary

Listen to a Dynamic Summary of the Article

Created using NotebookLM AI tool

It is Friday night. A packed synagogue in one of the ultra-Orthodox neighborhoods of Jerusalem. Standing out in the crowd of men dressed exclusively in black and white are two armed soldiers in the khaki-green of the Border Police. This rare sight elicits whispers and stares. For most of the congregation, this is the first time they have seen a soldier in synagogue. A few of the worshippers, feeling ill at ease, approach the rabbi and express their dissatisfaction. The vast majority of them welcome the soldiers with warmth. They are friends of Staff Sgt. Yaakov Krasniansky, who lived in the neighborhood and was killed in the battle for Kibbutz Nahal Oz on October 7. They were invited to the synagogue by the bereaved family and the community’s rabbi.

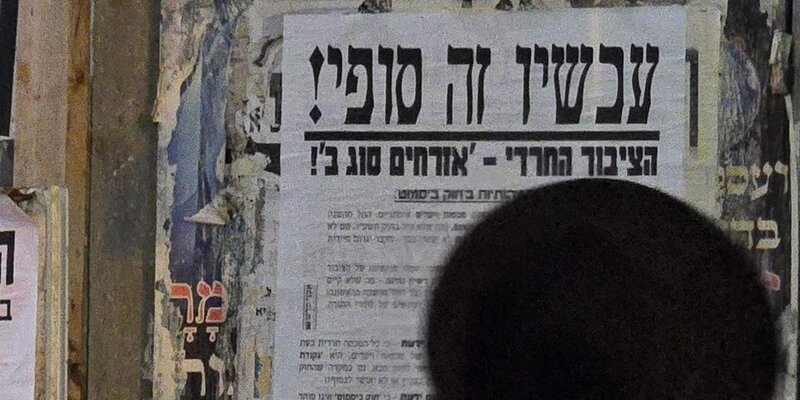

Until October 7 – the Shabbat morning of the joyous Jewish festival of Simchat Torah – such a scenario would have been almost unimaginable. However, the profound processes of change that ultra-Orthodox society in Israel has been undergoing in recent years – processes that may not have been immediately visible to the casual observer – have been accelerated by the atrocities committed by Hamas in the Gaza-border communities. Some are even happening in the open. A wave of solidarity and social mobilization has swept over Ultra-Orthodox society, reflecting a new mood – but it is hard to predict whether this will continue in the future. Yeshiva students spent time on the intricacies of the threads and knots on the prayer shawls that they sent to frontline soldiers; girls from seminaries rallied round to help farmers in the south; and, for the first time, ultra-Orthodox women volunteered on IDF bases. At the same time, there was a large uptick in the number of ultra-Orthodox volunteering for reserve duty through a three-month program designed for people who had previously been exempt from military service.

Alongside these manifestations of solidarity and mobilization, there are tragic stories about bereaved families. While there are no official figures, the Out for Change organization says that 14 of the fallen IDF soldiers thus far are former members of ultra-Orthodox society. That is in addition, according to the group, to five who were killed at the party on Kibbutz Re’em.

It is important to note that the lack of official data stems from the fact that it is almost impossible to define who counts as a former member of the ultra-Orthodox community. Are they only “former members” if they have adopted an exclusive secular lifestyle or does it also apply to someone who has merely changed the type of skullcap they wear – and has remained part of the religious, faith-based world, with all that this entails in terms of integration and Israeliness. The numbers are not negligible: a study from 2021 found that the rate at which people aged between 20 and 64 leave ultra-Orthodox society has fluctuated around 13 percent in recent years (compared to almost zero two or three decades ago) and that the rate among young people is even higher.

Either way, the fact that former members of ultra-Orthodox society have fallen in war intensifies that society’s direct contact with issues that it generally prefers to ignore – issues such as IDF recruitment, abandoning the religious lifestyle, relations with a relative who has left yeshiva and so on. Bereavement forces them to address these issues: mourning mingles with feelings of guilt and grief, appreciation and gratitude, and has managed to shake even the most firmly held ultra-Orthodox beliefs. It also creates some impossible dilemmas for ultra-Orthodox families, the first and most immediate of which is burial: a full military ceremony, which would honor the fallen soldier’s choice to become a fighter in the IDF but would also amplify that decision to the outside world – or a religious ceremony at a civilian cemetery, which would be conducted according to the rules of the community but would ignore the deceased’s choices.

The Krasniansky Family | ‘The Rabbi Had No Doubts’

.jpg)

News of the death of 23-year-old Yaakov Krasniansky spread quickly through the Jerusalem neighborhood of Ramot. The successful, strong and heroic son was no more. No one could process the news that he had been killed, but there were tough decisions that needed to be made quickly. What would the funeral service look like? Who would speak? Where would he be buried? What kind of ceremony?

Krasniansky was an exceptional student at the Or Yisrael yeshiva, but, at the age of 17, he decided to transfer to a high-school yeshiva so that he could complete his matriculation exams. Thereafter, he joined the IDF and served in the Border Police’s undercover counterterrorism unit. Shortly before his death, he extended his service by a few more months. “It wasn’t what my parents wanted, but they supported him throughout the whole process, from the very beginning,” Yaakov’s sister Or tells Shomrim.

The question of how to bury a young person who has left ultra-Orthodox society and joined the IDF is a weighty one. Among the considerations are the fact that military cemeteries are not run by the ultra-Orthodox burial society and that burial in a military cemetery broadcasts the son’s decisions to the world.

Or, however, says that her parents did not hesitate for a second; they wanted their son to be given the honor he deserves. “They see him as an Israeli hero in every respect and are incredibly proud of him,” she says. Her parents did not dwell on the social ramifications, she insists. Although they were firm in their minds that he would be buried at the military cemetery on Jerusalem’s Mount Herzl, they still consulted with their rabbi. “My mother asked if it was alright. Not that he be buried on Mount Herzl, more about the military ceremony and the barrages of missiles,” she adds. “The rabbi had no doubts. He told me that he has faith in the IDF rabbinate. That whatever they decide to do is alright. They can lay wreaths and flowers. He deserves to be honored in this way. There wasn’t even a moment’s doubt that he would be buried in a military ceremony and that was the right way to do it.”

But the parents’ decision was not the end of the story. Just hours before the funeral, a group of ultra-Orthodox radicals came to the family home. Nobody in the family knew these people, but they said that they would “take care of everything.” What they meant was that they would arrange the funeral at Har Ha’Menuchot Cemetery, since burial on Mount Herzl was “not a good idea.” Yaakov’s parents simply could not understand why these people thought they had the right to interfere in their affairs. “They stormed into the house,” says Or. “My parents told them they had already spoken to the rabbi and that they weren’t interested and they should leave.

Staff Sgt. Yaakov Krasniansky was laid to rest in a full military ceremony on Mount Herzl. His funeral was attended by many residents of the neighborhood in which he grew up, including the community rabbi, who tearfully eulogized him over his grave.

The Mittleman Family | ‘There Were Israeli Flags and Representatives from the Army’

The case of Sergeant David Mittelman, who fell in the battle for Kibbutz Kissufim, is different. The stormy weather and technical problems make a telephone conversation with M. – a close friend of David’s who also left ultra-Orthodox society and now serves in a front-line unit. There’s a strong wind blowing which makes it hard for us to hear each other but M. insists we keep talking. It’s important for him that Mittleman’s story is told. The fighter from the Golani Brigade was “a guy who loved to fool around – but knew how to be serious when he needed to be,” according to M.

Mittleman, who was 20 when he was killed on October 7, was raised in Modi’in Ilit – an ultra-Orthodox city in the West Bank – and was on a typical ultra-Orthodox path – until he decided to leave his yeshiva. He joined the army as a ‘lone soldier’ and lived in an apartment provided by Osey Chail, an NGO that provides support for soldiers from an ultra-Orthodox background. The group also found him an adoptive family on Rosh Tzurim, an ultra-Orthodox kibbutz in the West Bank. “David was not a guest. He was one of us,” his adoptive mother, Yael Ruzievich, said in an interview with Makor Rishon. “He used to take the family dog out for walks and played backgammon with the kids. We took him to the train station and to the doctor whenever he needed.”

Mittleman’s ultra-Orthodox family did not want a military funeral. “Anyone who could talk to his parents did so. We tried to persuade them. We asked that they at least let us put a military headstone on his grave so that there would be some indication that he was a soldier, that anyone passing his grave would see it – but we weren’t successful,” M. adds.

Thousands of people attended Mittleman’s funeral – many of them from Modi’in Ilit. “There were Israeli flags, there were representatives from the army and it was a very respectful funeral,” says Lavie Ruzievich, one of Mittleman’s adoptive siblings.

The story of David Mittleman’s funeral made waves among people who have left the ultra-Orthodox and religious lifestyles – and in Israeli society at large. As a result, many formerly religious soldiers signed living wills and the IDF issued clarifications about its policies on the matter to prevent a repetition.

“For their own reasons, they decided to give him a civilian funeral. It was hard for all of us,” says M. “David was killed because he was a soldier and not for any other reason. He was killed because he fought for this country. He chose to protect the state and there is a right way to honor anyone who so chooses. Unfortunately, he was not afforded that honor. This leaves a nasty scar in our hearts.”

The media attention that the manner of their son’s funeral garnered led the Mittleman family to speak about the great pain they were in and the fact that, as they see it, their loss has been used to polarize and radicalize Israelis. “People said that we did not sit shiva for our son – and that felt like he had been killed again,” the parents said in an interview after the seven-day mourning period.

Mittleman’s friends decided to find alternative ways of memorializing him. “We lived with him for a long time. We were a significant part of his life and he was a significant part of ours,” says M., adding that “the family comes first and I believe that they have the right to decide whatever they want. We will try to memorialize him in our own way and we will do things that are more connected to who he was in recent years.”

The Elmakayes Family | ‘As Far As Values Go, He Was More Than Ultra-Orthodox’

The family of Master Sergeant (Res.) Benjamin Elmakayes came to Israel from France for his upcoming wedding. Instead of walking him down the aisle, they accompanied him on his final journey. Elmakayes, a 29-year-old soldier in the Combat Engineering Corp’s 8219th Battalion, was killed in battle in central Gaza on November 8.

Elmakayes immigrated to Israel without his family in order to study at a yeshiva in the Holy Land. After deciding that the yeshiva world was not for him, he moved to the Zionist Youth Village School before joining the IDF as a lone soldier. When his mandatory service ended, he found a job as a security guard.

The Elmakayes family also found themselves struggling with the issue of Benjamin’s burial and funeral. In the end, they decided to hold a full military service on Mount Herzl. At the same time, the vexed question of leaving ultra-Orthodox society came up. Should mourners ignore that part of the fallen soldier’s life and focus exclusively on who he was as a yeshiva student? Should people addressing the funeral only talk about those things that are acceptable in ultra-Orthodox society and ignore the differentness? Or should they accept the change and the choices he made during his life?

The family sat Shiva at the Theatron Hotel in Jerusalem. The space set aside for mourners was divided down the middle – women on one side, men on the other. In the women’s section sat Revital, Benjamin’s ultra-Orthodox aunt. She raised him like a son since he immigrated to Israel. Her silence only amplifies her pain. “He was not ‘not ultra-Orthodox, God forbid,” she finally says. “He was religious, he wore tefillin and observed the Shabbat. He did not study [Torah] every day but he adhered to the commandments. He prayed three times a day, recited psalms and wore black-and-white occasionally. He was incredibly righteous.”

“He was so strong,” adds Yehudit, Revital’s daughter. “He was religious but being in the army isn’t like sitting around studying Torah. As far as values go, he was more than ultra-Orthodox. He came to visit us once a week, on Shabbat and Jewish holidays.”

Revital recalls the holy places that Benjamin especially loved working as a security guard, such as the Mount of Olives and Hebron. “His greatest aspiration was to defend the Land of Israel and all the People of Israel,” she says.

On the other side of the lobby of the hotel in Jerusalem sits Benjamin’s French family – without gender segregation. The conversation jumps between stories that Benjamin’s fiancée tells about his time in the army to his grandmother’s tales of his exploits as a child. It appears that the ultra-Orthodox dilemmas that Benjamin’s aunt spoke of are not present on the French side of the room, where there is only pain and mourning over the fact that Benjamin is no longer here. That gulf, it seems, between branches of the same family, the Israeli and French branches, encapsulates the entire story of ultra-Orthodox bereavement.