How Ben-Gvir Derailed Israel’s Flagship Program Combating Violence in the Arab-Sector

Youth protection instructors deployed to neighborhoods plagued by violence and vandalism; rapid intervention to halt cycles of family revenge; and a coordinated mechanism linking the community, police and State Attorney’s Office - these were among the key tools of Stop the Bleeding, the anti-crime initiative launched by the Bennett-Lapid government in seven severely affected Arab communities, including Umm al-Fahm, Taibeh, Lod and Rahat. But since taking office, National Security Minister Itamar Ben-Gvir has forced the American Jewish Joint Distribution Committee out of the program, slashed budgets, dismissed staff, and left the initiative without clear leadership. Meanwhile, murder rates continue to soar. In response, Ben-Gvir’s ministry has attempted to shift the blame onto the Finance Ministry. A Shomrim investigation.

Youth protection instructors deployed to neighborhoods plagued by violence and vandalism; rapid intervention to halt cycles of family revenge; and a coordinated mechanism linking the community, police and State Attorney’s Office - these were among the key tools of Stop the Bleeding, the anti-crime initiative launched by the Bennett-Lapid government in seven severely affected Arab communities, including Umm al-Fahm, Taibeh, Lod and Rahat. But since taking office, National Security Minister Itamar Ben-Gvir has forced the American Jewish Joint Distribution Committee out of the program, slashed budgets, dismissed staff, and left the initiative without clear leadership. Meanwhile, murder rates continue to soar. In response, Ben-Gvir’s ministry has attempted to shift the blame onto the Finance Ministry. A Shomrim investigation.

Youth protection instructors deployed to neighborhoods plagued by violence and vandalism; rapid intervention to halt cycles of family revenge; and a coordinated mechanism linking the community, police and State Attorney’s Office - these were among the key tools of Stop the Bleeding, the anti-crime initiative launched by the Bennett-Lapid government in seven severely affected Arab communities, including Umm al-Fahm, Taibeh, Lod and Rahat. But since taking office, National Security Minister Itamar Ben-Gvir has forced the American Jewish Joint Distribution Committee out of the program, slashed budgets, dismissed staff, and left the initiative without clear leadership. Meanwhile, murder rates continue to soar. In response, Ben-Gvir’s ministry has attempted to shift the blame onto the Finance Ministry. A Shomrim investigation.

Protestors in Umm al-Fahm after the murder of Nidal Ighbariya, a journalist and resident of the city, in 2022. Credit: Reuters

Shuki Sadeh

October 26, 2025

Summary

Listen to a Dynamic Summary of the Article

Created using NotebookLM AI tool

Last Wednesday – just as Israel was getting into a post-High Holidays routine and was still catching its breath after the release of 20 living hostages, and a ceasefire after the two-year war in Gaza – two people were shot dead in broad daylight on Route 433 in the center of the country. One of the fatalities was Sergei Matatov, an innocent bystander who left behind a pregnant wife and a one-year-old daughter. According to police, the background to the shooting was a conflict between rival criminal gangs – in this case, from Lod. On the very same day, Nadal Masaadeh, a father of four from Kafr Yasif, was gunned down at the gates of the school where he worked as a security guard. That day ended with news that Dr. Ziad Abu Abed, a 27-year-old doctor from Rahat who worked at Soroka Hospital and who had been wounded in a shooting earlier this month, had succumbed to his injuries. The next day, three more people were murdered – two in northern Israel and one in the Negev.

Each of the past three years – since the establishment of the current government and the installation of Itamar Ben-Gvir as minister of national security – has seen a similar spike in homicides. Over this period, the number of murders in the Arab sector has doubled compared to previous years, with more than 200 homicides a year and thousands of injuries. (See graph.)

Ahmed (not his real name) is a resident of Umm al-Fahm in his twenties. He became a victim of this bloody reality last year, when he was shot 17 times; several of the bullets hit his legs. The incident happened in the Al-Battan neighborhood of the city, where Ahmed was working as a youth protection instructor as part of the “Stop the Bleeding” campaign jointly launched by the Ministry of National Security, the State Attorney’s Office and the Israel Police. As a youth protection instructor, Ahmed’s job was to be present at those places where young people gather and could engage in antisocial behavior, especially in the evenings, and try to prevent any incidents from becoming violent.

Mohammed Sami, who runs the project on behalf of Umm al-Fahm municipality, says that within two months of Ahmed starting work, the number of complaints from residents of those neighborhoods fell from 65 a month to just five. Moreover, he says, the nature of the calls also changed; previously, they complained about vandalized facilities, assaults, or the open consumption of drugs, they now mainly focused on noise violations. Early in 2025, however, it was decided to cut the budget of the Israel National Authority for Community Safety, which operates as part of the Ministry of National Security. Notwithstanding the injuries he sustained in 2024, Ahmed was fired, along with another youth protection instructor. Other instructors working in the same project had their hours cut or were forced to move to part-time positions.

“We thought we had cracked the code, but then came the cuts, which impacted not only our staffing, but also our ability to publish in the media"

What happened to Ahmed on a personal level could serve as a metaphor for the entire project. On the one hand, the program had a lot of potential and was accompanied by much goodwill. On the other hand, the financing was held back and decisions were imposed from above, from the political echelon, which led to the program’s slow death and to the people on the ground becoming disillusioned. “In Umm al-Fahm, there are very different kinds of people,” says Sami. “People who are trying to live normative lives and criminals – the kind of people in the gray area. We are fighting here for a normal and quiet lifestyle, which is a massive challenge.”

According to Sami, as part of the “Stop the Bleeding” program, eight places in Umm al-Fahm were defined as hotspots – places where authorities believe that acts of violence and/or vandalism were more likely. “We managed to ‘cool down’ six of them by installing security cameras and deploying staff,” he says. “We thought we had cracked the code, but then came the cuts, which impacted not only our staffing, but also our ability to publish in the media. We had a budget of 35,000 shekels (around $10,600) for videos and content on social media that was supposed to influence young people and send anti-violence messages, but that was slashed to just 10,000 shekels.”

Hotspots and cycles of revenge

Eight Arab localities across the country are running pilot versions of the “Stop the Bleeding” program. It was launched in 2022, as part of Government Resolution 549, which had been passed the previous year by the Bennett-Lapid government. Included in that resolution was a decision to allocate 2 billion shekels (about $600M) over five years to various plans aimed at reducing crime in Arab society; “Stop the Bleeding” was one of those programs. The communities selected for the pilot were Turan, Tamra, Jisr al-Zarqa, Umm al-Fahm, Taibeh, Lod and Rahat – communities which were experiencing (and some of which are still experiencing) extraordinarily high homicide rates in the years before the program was launched. Next year is supposed to be the last year of the pilot scheme, after which authorities will decide whether and how to extend it.

The idea behind “Stop the Bleeding” is to home in on a specific area, launching a three-pronged effort focused on prevention, enforcement and community work; the plan also relies on cooperation between the local authority and the government on three levels: the National Authority for Community Safety, the State Attorney’s Office and the police. It is worth noting that, at the start of the project, there was also an academic interest; coordinated by the Joint (the American Jewish Joint Distribution Committee), the Institute of Criminology at the Hebrew University of Jerusalem was also involved – until its activities were curtailed by Ben-Gvir (on which, more later).

Hotspots are a key concept within the project. “Each community has a project manager and one of their jobs is to identify hotspots where violent incidents happen,” says Wisal Raed, Coordinator of Rehabilitation and Financial Inclusion at the Sikkuy-Aufoq NGO, who has researched implementation of the project. “If we identify vandalism or drug or alcohol abuse, we send out a youth protection instructor to deal with the phenomenon and to forge a connection with the young people and to try and find them a framework or some kind of activity on the ground. Sometimes, those places also need a visual upgrade. In Rahat, for example, there were not enough facilities in public spaces. There were also a lot of piles of garbage, which people would use to hide weapons.”

“Each community has a project manager and one of their jobs is to identify hotspots where violent incidents happen,”

Another effort focused on personally identifying known offenders, both those recently released from prison and those with historical police records, for the dual purpose of enforcement and guiding them into suitable vocational training or any path that takes them away from a life of crime. Among the newly hired professionals are six prisoner rehabilitation coordinators, employed by various local authorities, which has led to an increase of 16 percent in the number of former inmates treated by the bolstered staffing, according to a report by the Abraham Initiatives and the Citizens’ Empowerment Center in Israel published in May 2024. One such case, according to Sami, involved “a 25-year-old man who was close to a criminal organization and was released from prison. Our coordinator signed him up for a vocational course, to show him how he could open his own business and get back on a more positive path. But the criminal gangs are still trying to tempt him back.”

Another system being used is taken from the world of prevention and is known as the Soroka Model. It is a collaborative effort between the Rahat municipality and Soroka Hospital in nearby Be’er Sheva. According to a senior official from the State Attorney, the moment anyone from Rahat arrives at Soroka with a gunshot wound, the case is referred to community officials in the town, who immediately talk to the victim and their relatives in an effort to lower the chances of a violent response. There are plans to implement a similar model in January 2026, involving the Umm al-Fahm municipality and Emek Medical Center in Afula.

On the community level, efforts have also been invested in mediation between warring families. According to Waheed Alsanah, project director in Rahat, whenever there are people shot and wounded, he tries to mediate between the families and avert any possible revenge attacks. This process involves a third party who acts as a guarantor, even depositing money to prove their seriousness, and the outcome of the process is also made public to make it even more credible. Alsanah cites one example of a young man with absolutely no connection to criminal activity who was shot by a member of a rival clan. According to Alsanah, members of those clans are now so close that they have even taken joint vacations to Morocco. “He doesn’t know exactly who it was that shot him, because that’s part of the process – but he knows he’s there,” says Alsanah. “A murder is a different story. Emotions are still running high and you can’t do anything. You try to arrange a truce and ensure that each family keeps its distance from the other.”

How ‘Stop the Bleeding’ Bled Out

Despite the promising start and the creative ideas, over the past three years, the program has failed to make a consistent and significant dent in the crime figures. Those garbage piles in Rahat, for example, were removed early on by the police – but soon reappeared. “In late 2022, the police launched two major operations to locate weapons stashed in garbage piles and took away more than 215 trucks full of garbage,” says Alsanah. “Since then, however, nothing has happened. There are five garbage facilities in New Rahat. If you try to use one, people will come out and ask what you’re doing there, because there are weapons in there. There is no clear ownership over the land, so the municipality is limited in what it can do. In effect, the state has abandoned that land.”

Community mediation efforts also sometimes fall short, certainly when the police presence is insufficient. Murad Ammash, the head of the Jisr al-Zarqa regional council, spoke to Shomrim about the tragic case of Rosette Jarban, a 36-year-old woman who was shot and killed when returning from a trip to the beach. “It’s part of a conflict that started a year ago,” he says. “Two masked men shot a young man whom they accused of torching their car. The victim’s brothers tried to avenge him, burning houses and cars – and the conflict between the families continued. We made every effort to prevent that murder. Our Welfare Department and our residents. We told them: ‘The guilty parties are under arrest. Stay home and don’t go to work.’ But they were hell-bent on revenge.”

Ammash adds: “Unfortunately, it doesn’t end with Jisr al-Zarqa. There are several reasons for this. It’s not just a question of the local authority working with residents. You need a massive police presence on the ground. Firearms are flowing in freely and, at the same time, there are conflicts between gangs of youths who operate like armed militia. The police know, everyone knows, but they can’t stop it.”

Two main turning points can be identified when looking for where the implementation of the plan went awry. The first occurred during 2023, shortly after he was appointed minister of national security, when Ben-Gvir decided that the Joint – a veteran nongovernmental body with years of experience working with various Israeli ministries – would be ousted from the program. He accused it of being a “left-wing organization.” Ben-Gvir did so despite the fact that the Joint was heavily involved in designing the program, in part on the understanding that Arab citizens would be more inclined to trust an NGO. Another significant ramification of the Joint’s departure was in the field of data and assessment. The program was supposed to be accompanied by Prof. Badi Hasisi from the Hebrew University of Jerusalem’s Institute of Criminology. According to one government official well-versed in details of the program, since the Joint’s departure in November 2023, the program has had no academic follow-up.

Following the removal of the Joint, the plan floundered in each location according to that authority’s economic state, but there was an overall sense that no one was running the show. Officially, the program was transferred to the auspices of the National Authority for Community Safety. That, however, is a relatively new body and is considered ineffectual. This is in part due to superfluous transfers between ministries – shortly after its establishment, it was subordinated to the newly created Community Empowerment and Advancement Ministry, before moving back to the Ministry of National Security – compared to other similar bodies. Some two months ago, Ronit Ovadia – the head of the authority – announced that she was stepping down and, since then, her position has been filled by her deputy.

“This program - along with other projects aimed at tackling violence in the Arab sector – was one of the best things to come out of the previous government,” says former police commander, MK Yoav Segalovich (Yesh Atid party), who also served as deputy Minister of Internal Security with special responsibility for the Bennett-Lapid government’s effort to combat violence in Arab society. “They claimed that the program was not enough, but, in practice, it became a dysfunctional program on the professional level. Nothing happened on the ground. They simply neutered the plan.” One government official confirms this: “The exit of the Joint set the program back significantly. Ben-Gvir found it hard to find people in his ministry to replace the Joint officials who had spearheaded the program, so it was severely affected.”

“They claimed that the program was not enough, but, in practice, it became a dysfunctional program on the professional level. Nothing happened on the ground."

The second turning point in the de facto death of the program was the budget cut of between 15 and 30 percent that was announced in early 2025. This kind of cut to the budget of the National Authority for Community Safety could have led to the closure of the “Stop the Bleeding” program but, as it is, it was a massive blow to the work of officials from the seven local authorities where it is being piloted. Most of the program’s budget – around 80 percent – goes on staffing: coordinators – like Ahmed, who was fired from his position in Umm al-Fahm – and other staff on the ground. Under these circumstances, each authority has to decide how it will deal with the cuts.

In Turan, for example, a community of 15,000 residents, the budget for the program in 2022 was 686,000 shekels. In May of this year, however, the cash-strapped local authority was forced to fire nine employees and the program has been dormant ever since. “We managed to hang on until May and then we decided to freeze the program,” says Hanan Sabah, head of the National Authority for Community Safety in Turan. “We have no resources. It’s all been halted: the work on the ground, the work with the State Attorney and the police.”

Sabah admits that she still has no idea what will happen with the program next year. “There was a drop in crime here and, in fact, we are back to 2018-2019 levels, before the crisis. But we cannot know how much of that was because of the program, because there was no assessment and measurement.” An official from the State Attorney believes that the program played a key role in reducing crime. “This is a community that got its act together. The ‘Stop the Bleeding’ program did intensive work. It isn’t just because of the [July 2021] truce. There was a huge amount of community work alongside serious enforcement. The State Attorney is still very heavily invested there and cares about what happens.”

‘It’s September and we still haven’t got the money’

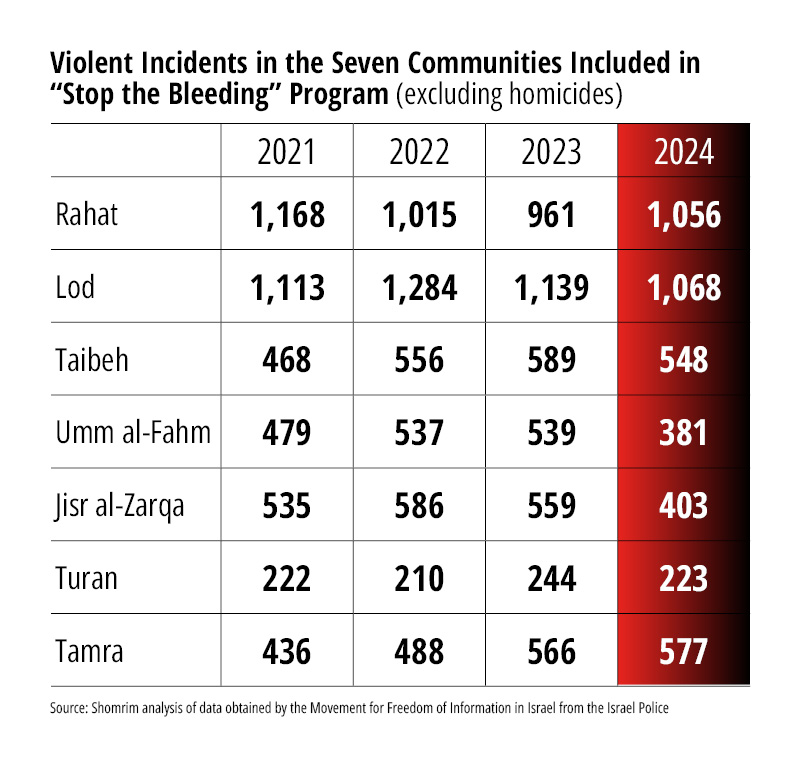

Caring, however, isn’t enough, and it’s not just in Jisr al-Zarqa that the violence continues unabated. Two of the seven communities where the program is being operated – Rahat and Lod – are ranked third and sixth, respectively, in the national crime and violence tables, which measure the number of victims in relation to the total population. These were the findings of a report published in August by the Movement for Freedom of Information, the Madlan website and N12 News, which collated data on violent attacks across the country. Shomrim analyzed that data in relation to the seven communities included in the “Stop the Bleeding” program and produced graphs showing violent incidents and homicides (see below).

The communities selected for the pilot were Turan, Tamra, Jisr al-Zarqa, Umm al-Fahm, Taibeh, Lod and Rahat – communities which were experiencing (and some of which are still experiencing) extraordinarily high homicide rates in the years before the program was launched.

These figures, which relate to the years between 2021 and 2024, do not show a significant downward trend. In some places, there is a slight increase in the number of criminal incidents, while in others there is a slight decrease; others remain steady. When it comes to homicides, there was a sharp rise in 2023 and 2024 in some of the communities using the program, as there was across Israel. “The goal of the program is to create a joint effort between various bodies,” says the same State Attorney official quoted above. “We have to think of other ways to resolve the conflicts. After all, in today’s world a post on Instagram can lead to a murder; or someone could get angry after a small accident and kill someone. Things can explode out of nowhere.

“In Taibeh, for example, the start of implementation of the model went well, but, at one stage, it started to regress – in part because there was no director for a long period. In the end, if you’ve got a good plan and you don’t manage to execute it, it’s a problem.” In Jisr al-Zarqa, too, incidentally, there were several months when the “Stop the Bleeding” program had no director on behalf of the National Authority for Community Safety. Recently, Haneen Maswaha Haj-Yahya was appointed head of the Arab division at the National Authority for Community Safety, a role that includes directorship of the program in Taibeh.

Sikkuy-Aufoq is preparing to publish a policy paper focusing on the program and based on interviews with project directors in the seven communities and with civil servants. According to details of the report shared with Shomrim, there are several impediments to implementation of the program, including in police work, community involvement and staffing limitations. The report will also highlight the failed connection between local authorities and the police, with local officials complaining that they were not getting updates and information from the police about the situation at known hotspots and elsewhere.

The paper will also raise the problem of recruiting improperly trained staff on the one hand, and the problems faced by local authorities recruiting qualified staff of any kind, given their poor socio-economic status, which prevents them from offering attractive salaries. Although the state is supposed to allocate a dedicated budget for the project – local authorities are still waiting for this year’s budget – none of them are wealthy enough to add to the salary from their own coffers. Similarly, in the event of a cutback or failure to transfer the money early in the year, it is up to the local authority to decide whether to extend its own credit.

“As far as officials from the government and the State Attorney are concerned, this is a flagship project,” says Rawyah Handaqlu who, until recently, served as head of the Union of Arab Local Authorities’ anti-violence campaign. “But there are gaps in perception when it comes to how the project should work. There are a lot of impediments and this project was unable to fulfill its potential and fell between the cracks. The Ministry of National Security didn’t take it seriously and undermined it. At Knesset committee hearings the program is referred to as a success, but that isn’t borne out by the figures. They ran the program as a pilot without stopping to think seriously for one minute about the future – and that says a lot, too.”

The fourth year of the program is about to end, even though, as mentioned, it has not worked continuously or fully during that period. Not only is it unclear whether the pilot will continue and whether it will be expanded to other communities, it is still to be determined whether it will operate at all next year. This is further evidence of how the current government is handling one of the most acute and pressing problems that Israeli society has faced in recent years.

“At its core, as we designed it, this is an excellent program that can help Arab society, which is going through very tough times,” says Ofer Toder, director-general of Umm al-Fahm municipality. “But it has two main problems. The first is budgets. We are in September and we still haven’t received the money to fund the program for the current year; we are operating according to the budgetary basis we have at City Hall. The second issue is uncertainty over the future. It’s extremely hard to work like that.”

Responses

The National Authority for Community Safety submitted the following response: “The ‘Stop the Bleeding’ project is a pilot with national potential, based on scientific knowledge and international experience, and has been implemented in Israel since 2022. The project is being carried out in seven local authorities, according to the focused deterrence model and the partnership model between the community, the police, and the State Attorney’s Office. The project includes detailed programs tailored to the needs of each locality. Every action is evaluated with the goal of creating an evidence-based doctrine for expansion and implementation in additional cities.

“The National Authority for Community Safety, which leads the initiative along with the Ministry of National Security, the Israel Police and the Ministry of Justice, has continued to operate in over 90 percent of local authorities, despite a budgetary delay spanning many months from the Ministry of Finance. This delay concerns the budget designated for Government Resolution 549 and, consequently, the funding for ‘Stop the Bleeding.’ Nevertheless, we are working to ensure the project’s continued advancement and the fulfillment of the program’s core objectives.

“The National Security Ministry recently signed a contract with the Institute of Criminology at the Hebrew University of Jerusalem for a process-based study, which constitutes a central pillar for impact assessment and continuous learning. In line with the policy of the national security minister, a dedicated subject matter manager was recently appointed to handle and oversee the issue. Additionally, the Ministry of National Security worked to fund a position within the State Attorney’s Office, alongside the allocation of a senior professional for this issue, who also operates on behalf of the Israel Police on this matter. The allocation of these designated positions was done in accordance with the policy of the Minister of National Security to establish the program as an integral part of these bodies’ activities.

“Regarding the budgeting, regrettably, despite repeated appeals from the Ministry of National Security to the Ministry of Finance, the issue has yet to be settled. We hope that the funds for the local authorities will be transferred by the Ministry of Finance promptly and settled with the local authorities. The National Steering Committee, which recently convened under the leadership of the Deputy Director General of the Ministry of National Security, and in cooperation with the Israel Police, the State Attorney’s Office, the Ministry of Justice and Prof. Badi Hasisi, will reconvene shortly to examine the continued development of the program for the coming years and in preparation for the continued implementation of Resolution 549.”

Israel Police response: “This is a project that was set up as a result of Government Resolution 549, under the leadership of the National Authority for Community Safety. The Israel Police carries out intelligence, operational and community initiatives in a continuous and extensive manner to prevent crime and enforce the law in Arab society in general and the communities involved in the project in particular, while coordinating closely with local authorities and government bodies. Information and assessment results are continually shared to help focus operations, both for the police and for the relevant local agencies. Crucially, the Israel Police is only one part of the comprehensive program that integrates many organizations.”

The Ministry of Finance responded: “In the 2025 budget, an exceptional budgetary increase of approximately 2.2 billion shekels was allocated to the Ministry of National Security and its subsidiary bodies. This addition, one of the largest granted in recent years, was agreed upon after prolonged negotiations and was intended to ensure a full budgetary response for the activities of the ministry and its bodies, including the activities of the National Authority for Community Safety. The allocation of resources among the various issues under the ministry’s responsibility, including the reduction in the budget for the National Authority for Community Safety, was carried out according to the priorities set by the ministry. Should the Ministry of National Security wish to change these priorities, it must do so according to accepted procedures.”