Exclusive: Israel’s Outgoing Government Approved a First-Ever Outreach Program to Progressive American Jews. Its Future is Now Shaky

After years of neglect by Israeli decision-makers, the outgoing government launched a first-ever initiative aimed at tackling the growing rift between the State of Israel and progressive Jews in the United States. Supporters of the project - revealed here for the first time - say that its importance lies in the fact that, for the first time, Israel will be officially cooperating with Conservative and Reform communities. Its detractors argue that it does not address key issues that are worrisome for its intended audience. Either way, the projects’ survival under the new government is at risk. A Shomrim exclusive

.jpg)

.jpg)

After years of neglect by Israeli decision-makers, the outgoing government launched a first-ever initiative aimed at tackling the growing rift between the State of Israel and progressive Jews in the United States. Supporters of the project - revealed here for the first time - say that its importance lies in the fact that, for the first time, Israel will be officially cooperating with Conservative and Reform communities. Its detractors argue that it does not address key issues that are worrisome for its intended audience. Either way, the projects’ survival under the new government is at risk. A Shomrim exclusive

.jpg)

After years of neglect by Israeli decision-makers, the outgoing government launched a first-ever initiative aimed at tackling the growing rift between the State of Israel and progressive Jews in the United States. Supporters of the project - revealed here for the first time - say that its importance lies in the fact that, for the first time, Israel will be officially cooperating with Conservative and Reform communities. Its detractors argue that it does not address key issues that are worrisome for its intended audience. Either way, the projects’ survival under the new government is at risk. A Shomrim exclusive

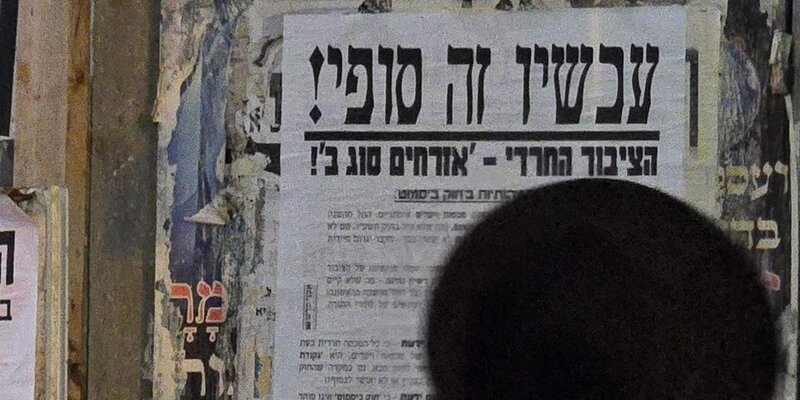

Photos: Reuters

Uri Blau

November 10, 2022

Summary

Listen to a Dynamic Summary of the Article

Created using NotebookLM AI tool

The rift between the State of Israel and progressive Jewish communities in the United States has widened significantly in recent years. Many reasons have contributed to it, including Israel’s treatment of non-Orthodox Jews, the stalemate in the peace process with the Palestinians, the close relationship between Prime Minister-elect Benjamin Netanyahu and former U.S. President Donald Trump, and more. Yet until now, most Israeli decision-makers have ignored the issue. By doing so, they disregarded the potential consequences of this crisis on Israel’s standing in the U.S. and the extent to which American Jews identify with the Zionist vision.

Now, Shomrim reveals that few months before the 1/11 elections, the outgoing Ministry of Diaspora Affairs launched a first-ever project to tackle the crisis. The internal ministry documents describing the issue leave no room for doubt: according to them, the process these communities are going is the result of the “internalization of the framework of a progressive discourse among an increasing number of Jews.” Urgent action is needed to rectify the situation because of the undermining of “Jewish identity in the United States” and the challenge to “Jewish communal togetherness and political vitality.”

To this end, the Ministry of Diaspora Affairs approved a budget of around 8 million shekels ($2.3 million) for the “Project to Strengthen the Bond with Liberal Communities in Israel and North America.” At the heart of the project is a first-ever collaboration between Israel and Reform and Conservation communities as a means of bringing progressive communities closer to Israel, in part by launching programs that would bring young North American Jews to study in Israel, community activity and so on.

Critics of the project argue that it is far from perfect since it is trying to walk on political eggshells in Israel. They explain that the program does not deal directly with any of the issues at the heart of the rift between Israel and American Jews. Nonetheless, even the harshest critics of the plan agree that it is hard to overstate the importance of this first-ever official collaboration between the Jewish state and communities that make up more than 3.5 million Jews.

Either way, the outcome of this month’s Israeli election has thrown everything into disarray and there is great concern among American Jewish communities about future developments. Leaders of these communities opted not to respond directly to questions about the future of the project, but the official responses they published in the aftermath of the election says a lot. The Reform Movement, for example, said it was “profoundly concerned” by the possibility that Itamar Ben-Gvir and Bezalel Smotrich could be given ministerial positions. “Their platforms and past actions indicate that they would curtail the authority of Israel’s Supreme Court and inhibit the rights of Israeli Arabs, Palestinians, members of the LGBTQ+ community, and large segments of Jews who are non-Orthodox,” the statement said.

The Reform Movement said it was “profoundly concerned” by the possibility that Itamar Ben-Gvir and Bezalel Smotrich could be given ministerial positions. “Their platforms and past actions indicate that they would curtail the authority of Israel’s Supreme Court and inhibit the rights of Israeli Arabs, Palestinians, members of the LGBTQ+ community, and large segments of Jews who are non-Orthodox,” the statement said.

‘There’s No Difference Between Liberalism and Jewish Values’

The Jewish community in the United States measures around 7.5 million people, according to a 2020 survey conducted by the Pew Research Center, making it the second-largest Jewish community in the world, behind only Israel. The report found that 73 percent of adult Jews in the United States see themselves as Jews by religion, while the remainder defines themselves as Jews of no religion (people who identify as atheist or agnostic in terms of their religious affiliation). The largest stream of Judaism in the U.S., according to the survey, is the Reform Movement (37 percent of Jews belong to this stream), followed by the Conservative Movement (17 percent), the Orthodox Movement (9 percent) and other streams, which make up 4 percent. In total, 32 percent of Jewish Americans are not affiliated with any stream of the religion.

The survey also included statistics about Jewish Americans’ relations with Israel. The survey found that six in every 10 American Jewish feel some kind of emotional connection with Israel, and eight in 10 says that “caring about Israel” is a significant part of being Jewish, but this kind of support is prevalent mainly among Orthodox Jews or those who identify as Republicans. Among Jews who vote for the Democrats, for example, a majority opined that the United States is too supportive of Israel. The survey also found that only one-third of American Jews believe Israel is sincerely attempting to reach a peace agreement with the Palestinians and that one in 10 U.S. Jewish supports the BDS movement against Israel.

Dr. David Barak-Gorodetsky is the head of the Ruderman Program for American Jewish Studies at the University of Haifa. His research has looked at the relationship between religion and politics in American Zionism, the Reform Movement in the United States and Israel, and the question of religion in relations between Israel and the Diaspora.

“The alienation of progressive Jews from Israel is an ongoing process that has reached a peak in recent years,” he says. “It is a complex process, the causes of which are not dependent exclusively on Israeli policy, but on general trends in American society and internal trends with the Jewish community.” Barak-Gorodetsky says that the problem is severe, but that data about the erosion of support for Israel makes it hard to define the problem precisely. On the one hand, he says, the Pew report shows that around 80 percent of American Jews claim that Israel is important to them. At the same time, he points to a finding from a survey conducted after Operation Guardians of the Wall in May 2021, which found that around a quarter of American Jews agree with the statement that Israel is an apartheid state.

Barak-Gorodetsky adds that, over the years, progressive Judaism in the United States has adopted liberal values as the focus of its Jewish identity. “From the perspective of a young Jewish American raised on the concept of ‘Tikkun Olam,’ there is no difference between liberal values and Jewish values. This is a source of great tension with Israel. In liberal Jewish-American society, especially among the young generation, there is an intractably liberal worldview, and there are almost no encounters between conservatives and liberals, which is more characteristic of Israeli society, which is by its nature more conservative. Therefore, the intersection with Israel is paved with profound misunderstandings. Telling young Jewish Americans that they must safeguard the future existence of the Jewish people by only marrying someone of the Jewish faith is seen as racist toward others. Young liberal Jews see themselves first and foremost as part of the liberal camp and are obligated to its values, and only then do they see themselves as part of the Jewish People, with a broader Jewish history.”

Rotem Oreg is the young Israeli behind the ‘Washington Express,’ an online Hebrew platform covering and analyzing American politics and foreign policy. Oreg recently founded the Israeli-Democratic Alliance, which seeks to forge a connection between Israelis and Democrats in the U.S. based on shared liberal values. “In Jewish communities and synagogues in the United States,” he explains, “there was once talk about ‘The Zionist dream’ – a land of milk and money and a model society. That wasn’t an invented narrative – it came from the true Zionist ethos, which was very relevant in the first decades of Israel’s existence.” In recent years, he adds, that dream disappeared for many American Jews, because of the stagnation of the peace process or because of issues of state and religion and minority rights. “Young Jews leave the relatively closed communities they grew up in and find themselves on campuses, which are a very progressive environment. And it is there that they see a side of Israel that they have not usually been exposed to. Suddenly, they realize that Israel also does things that are not cool. For them, it’s a real upheaval.”

Rotem Oreg, the Israeli-Democratic Alliance: “Young Jews leave the relatively closed communities they grew up in and find themselves on campuses, which are a very progressive environment. And it is there that they see a side of Israel that they have not usually been exposed to. Suddenly, they realize that Israel also does things that are not cool. For them, it’s a real upheaval.”

‘Being on the Right Side of History’

As mentioned above, the reasons for this alienation are varied, but those interviewed for this article agreed that the Palestinian issue is at the top of the list of concerns. Barak-Gorodetsky explains that, in recent years, the progressive discourse in the United States has focused on race and discrimination. “This is fundamentally a phenomenon that sought to address a very real and critical problem in American society, and Jews naturally feel that they are part of that struggle. The problem is that in this process, Jews are identified as ‘white’ and enjoying ‘white privilege,’ which erodes the legitimacy of the fight against antisemitism (which, as a whole, is on the increase) since racism cannot ostensibly be directed against white people. This discourse also has ramifications on the view of the Israeli-Palestinian conflict as racial rather than political, national, or religious. In this spirit, among liberals in the United States, identifying with Israel or with Zionism is seen as racist, and liberal Jewish Americans want to distance themselves from it as much as possible. Within this context, there is a great deal of pressure on progressive Jewish Americans to steer clear of Israel, which is unilaterally perceived as the discriminator in the Palestinian context. There is little understanding of the complexities of the Israeli-Palestinian conflict, rather a loud call – especially on campuses – to take a side, to be, as it were, on ‘the right side of history’.”

Rabbi Jacob Blumenthal, CEO of the United Synagogue of Conservative Judaism, was rather more cautious in his comments when he was interviewed before the election. “Our community is very diverse regarding people’s approach to Israel, so we are used to talking with people who have differing views on Israel, on the Israeli government and its policies. Our movement supports Israel and Zionism, but our views on the settlements and religious pluralism [in Israel] are a challenge,” he says. “We have found that the current government is attentive to us, but it is in a deadlock with regard to genuine progress because of the political situation in the country.”

Another key issue is Israel’s relations with the Reform and Conservative streams of Judaism, with which many American Jews are affiliated. When the Israeli government reneged on the so-called Kotel compromise, which was supposed to see the establishment of an egalitarian prayer area for men and women in the southern part of the Western Wall Plaza, it was seen as an excellent example of the kind of insult that these communities have suffered from Israel.

“The years of discrimination against liberal streams of Judaism in Israel not only harms the Israeli public’s faith in the religious establishment but also has external ramifications and causes strategic damage to the connection between Israel and the Diaspora,” Blumenthal wrote in a joint op-ed with Rabbi Rick Jacobs, the leader of the Reform Movement in the United States.

Jo-Ann Mort is a Jewish PR specialist who works extensively with progressive organizations and communities in the United States. She says that Israel’s treatment of mixed couples, which are very common in these communities, only exacerbates the frustration over the religious issue. “As soon as they arrive at the airport, at the security checkpoint, they ask, ‘Are you Jewish?’ and ‘When did you celebrate your bar mitzvah?’ You are labeled suspicious and they make you feel uncomfortable. That leaves a bitter taste and makes you wonder if you are even welcome in Israel.”

Jo-Ann Mort, Jewish PR specialist: “As soon as they arrive at the airport, at the security checkpoint, they ask, ‘Are you Jewish?’ and ‘When did you celebrate your bar mitzvah?’ You are labeled suspicious and they make you feel uncomfortable. That leaves a bitter taste and makes you wonder if you are even welcome in Israel.”

Not a Word about the Palestinians or Religious Discrimination

As mentioned, part of the alienation felt toward Israel stems from significant social upheavals in the United States, such as the #metoo movement and the Black Lives Matter demonstrations, which affect the expected treatment of minorities and various groupings in society. This process has harmed Israel’s image among the general American public and has seeped over into the Jewish communities.

Israel has not been oblivious to the changes in American public opinion, and over the years it has invested time, effort, and money in hasbara campaigns (such as the appointment of Noa Tishby as a pseudo-ambassador for Israel’s hasbara efforts) and in struggles to promote the Israeli narrative. For example, the Ministry of Strategic Affairs spent huge sums of money tackling what it called the “delegitimization” of Israel and tried to combat the boycott, divestment, and sanctions (BDS) movement. In contrast, Israeli governments over the years – most of which were under the leadership of Benjamin Netanyahu – opted not to deal with the impact of these social changes on the Jewish communities.

Given all of the above, the contents – or lack thereof – of the Ministry of Diaspora Affairs project make a rather surprising reading. Phrases like ‘Palestinians,’ ‘settlements,’ ‘Western Wall,’ ‘equality,’ ‘mixed marriages,’ and many other issues central to the disagreements with American Jewry are simply not there.

The document opens with reference to a survey conducted by the Reut Institute, a nonprofit policy think tank, which found that the adoption of a framework of progressive dialog among a growing number of American Jews was undermining Jewish identity in the United States. It is worth mentioning another paper published by the Reut Institute on the issue was given the Hebrew title “The Crushing Progressive Discourse” – which, it could be argued, makes the creation of any kind of dialog with progressive all the more difficult.

Either way, the Ministry of Diaspora Affairs explains how, despite the alienation of many liberal Jews from Israel, “liberal communities in the U.S., especially the Conservative and Reform movements, which make up the majority of community organizations, could provide a significant solution to an ever-growing problem.”

According to the document, the heart of the program is the connection “between Israeli communities and their counterparts in the Diaspora, which speak the same language and which have the ability to influence each other,” and that it will work “with various communities and age groups and will connect them with their Israeli counterparts, in order to influence and end the anti-Zionist trends that are starting to rise up among communities in the United States.”

In other words, cooperation with Reform and Conservative communities in the United States is supposed to create a kind of bridgehead to Israel, bring more American Jews to visit and study in Israel (especially high schoolers) and create a new dialog. And what about all those issues that are so antithetical to American Jews? The document does not mention them or specify how they will be resolved.

In a conversation with Shomrim, Diaspora Affairs Minister Nachman Shai said that, while previous governments had reservations about feelings of Reform and Conservative Jews, the ministry’s primary goal under his leadership was to foster closer relations with them. According to Shai, the distance between Jews in the United States and Israel is a difference in values, “so the outgoing government was very important to them since it represented values that are important to them and us, such as diversity, representation for minorities, and so on (…) we want to show that we do share common values.”

Shai says that his ministry, in cooperation with other bodies, is investing tens of millions of shekels to forge relations with Jewish students and high schoolers on 400 campuses across the world. “We recognized that we have to invest in high school students as well. So, we decided to join forces with their programs [the other bodies] to bring them to Israel so that we can integrate content about Israeli issues and Judaism in the school curriculum in the United States.”

This approach, as presented by Shai, has come in for harsh criticism. Libby Lenkinski is vice president for public engagement at the New Israel Fund, and her positions align fairly closely with liberal and progressive communities in the United States. “Treating the problem as if it was a public relations problem would be a mistake,” she says. “Progressives aren’t dumb. And when you tell people, ‘Look at the Pride Parade in Tel Aviv’ to highlight Israel’s treatment of its gay communities, it doesn’t stop them from thinking and talking about the things that really bother them, like the occupation and Israel’s treatment of the Palestinians.”

The Ministry of Diaspora Affairs sees things rather differently. From the ministry’s perspective, a project that appeals to liberal Jews in the United States has an added value that may even be more significant than the original goal: the first-ever cooperation with Reform and Conservative organizations in the United States. Indeed, the Reform Movement, which was a key partner in drawing up the ministry’s plan, is trying to see the glass as half full. “We view the Ministry of Diaspora Affairs as a partner to our cause,” says Rabbi Josh Weinberg, the vice president of the Union for Reform Judaism, who is the organization’s chief in Israel. According to Weinberg, they are creating a leadership program through which “we will work together toward the values of a Jewish and democratic state: respect of others, freedom, justice.” In addition, he says, “we want to promote the value of love of Israel and the understanding that the State of Israel has a central role to play in our Jewish identities. We are happy to cooperate with the Israeli government to advance these efforts.”

Weinberg adds, “I cannot deny that there has been a distancing and a tendency, mainly among progressive communities, to see Israel as the antithesis of progressive values. That is why we have to make a concerted effort. I, for example, am promoting an initiative known as Zionism-Justice, involving activists in various fields who can meet their Israeli counterparts, who speak the same language in favor of equality, social justice, migration, the environment, LGBTQ rights and so on.”

“We’re not ashamed to say words like ‘occupation’ or ‘human rights,’ but I don’t think that everything necessarily lives or dies by that. I see a broader picture: we can talk about peace, about violations of human rights, about racism, but also about the positive things. I think that’s also important.”

Blumenthal says that the Conservative Movement’s cooperation with Ministry of Diaspora Affairs programs – which are fundamentally similar to those of the Reform Movement – are in the final stages of being approved. He adds that the project will represent the first time the Conservative Movement will receive money directly from the Ministry of Diaspora Affairs for activity outside of Israel.

Libby Lenkinski, vice president for public engagement at the New Israel Fund: “Treating the problem as if it was a public relations problem would be a mistake. Progressives aren’t dumb. And when you tell people, ‘Look at the Pride Parade in Tel Aviv’ to highlight Israel’s treatment of its gay communities, it doesn’t stop them from thinking and talking about the things that really bother them, like the occupation and Israel’s treatment of the Palestinians.”

Will the Ideological Rift Widen?

Some of the interviews for this article were conducted before the Israeli election on November 1, and some of the interviewees expressed concern for the future of the project if power were to change hands. Once the result of the election became clear, most of them declined to answer follow-up questions from Shomrim. Some explained that they prefer to wait to see what direction Israel will take and what will be decided with regard to the project before responding.

According to Shai, the new government would find it hard to cancel a project that has already been approved, but he also expressed his concern over a widening ideological-moral gulf between progressive Jews in the United States and Israel. This rift, he says, “could drive a wedge between Israel and large parts of the Jewish world and, in a broader context, between Israel and the Democratic Party, including many lawmakers.”

Before the election, Barak-Gorodetsky said, “in my opinion, as someone to whom the future of the Jewish people is important, the problem is urgent, and the Ministry of Diaspora Affairs’ initiative is to be welcomed. Will it be effective? It’s hard to say. Obviously, there is suspicion among progressives toward any plan that originated with the Israeli government. But that does not mean we should not try. There is a center ground among liberal Jewish Americans, not just fringes, and we need to strengthen the center and to provide it with intellectual alternatives to aid their understanding of the current situation.”