Revealed: Haredi Education Networks Siphoned $75.5 Million from Teachers’ Pay

Under-the-table payments, unsupervised money transfers, unregulated and unlicensed schools and classrooms, refusal to pay social benefits and much more: an analysis of several lawsuits filed by teachers from ultra-Orthodox education networks provides a rare glimpse into the culture of chicanery and misuse of state funds. While the Ministry of Education and the treasury prefer to turn a blind eye, the teachers are afraid to complain. ‘It’s all very scary here.’ A Shomrim investigation, published also in The Marker

Under-the-table payments, unsupervised money transfers, unregulated and unlicensed schools and classrooms, refusal to pay social benefits and much more: an analysis of several lawsuits filed by teachers from ultra-Orthodox education networks provides a rare glimpse into the culture of chicanery and misuse of state funds. While the Ministry of Education and the treasury prefer to turn a blind eye, the teachers are afraid to complain. ‘It’s all very scary here.’ A Shomrim investigation, published also in The Marker

Under-the-table payments, unsupervised money transfers, unregulated and unlicensed schools and classrooms, refusal to pay social benefits and much more: an analysis of several lawsuits filed by teachers from ultra-Orthodox education networks provides a rare glimpse into the culture of chicanery and misuse of state funds. While the Ministry of Education and the treasury prefer to turn a blind eye, the teachers are afraid to complain. ‘It’s all very scary here.’ A Shomrim investigation, published also in The Marker

MKs Moshe Gafni and Aryeh Deri. Photo: Reuters

Lir Spiriton

July 11, 2025

Summary

Listen to a Dynamic Summary of the Article

Created using NotebookLM AI tool

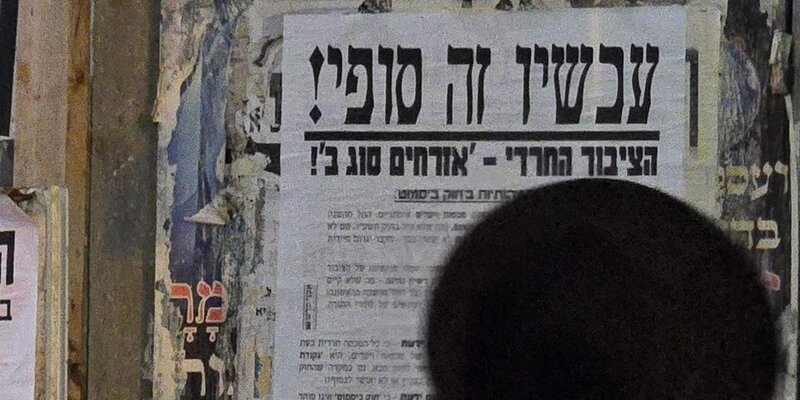

The never-ending political wrangling over the transfer of funds to private ultra-Orthodox education networks has made headlines in the Israeli financial press – yet has aroused precious little interest among the Israeli public. The issue is important because it is the only open and transparent method by which the Haredi education system is funded. The funding, no matter how generous it is, is not enough to ensure the survival of all of these networks and it is against this background that an entire culture has emerged – a culture of exploiting loopholes and cooking up all kinds of convoluted jiggery-pokery to bypass regulatory supervision, which is ridiculously lax in any case, and which ensures massive financial gain for the networks.

By its very nature, this world of scheming, wheeling and dealing is hidden from the public gaze, but – thanks to dozens of court actions, some of them class action suits – we are being given a rare glimpse at how it works in practice. The suits have been filed by teachers who claim that the ultra-Orthodox education networks used various means to make a profit from their meager wages. These teachers were paid by the Ministry of Education via the networks that employed them. They say that turning to the courts was far from easy and not something that they entered into lightly, but add that doing so has exposed them to threats and community pressure – and that they and their families are being paid to “pay” for their decision.

Analyzing these cases is like diving headlong into a rabbit hole: the court hearings often veer off in totally unexpected directions, revealing more and more layers of the tricks and deals. The Bnei Yosef school system, for example, is facing a class action lawsuit alleging that it failed to pay its teachers for “educator hours,’ which is time dedicated to non-frontal tasks. According to the lawsuit, over the past seven years the network has pocketed around 250 million shekels ($75.5M) by not paying its teachers for educator hours. While the hearings began by looking at the 250 shekels ($76) a week that was allegedly withheld from each teacher, they quickly deviated to allegations that teachers were paid in cash, that substandard classrooms were knowingly used to teach students, that certificates were forged, that schools were opened without the necessary authorization and so on. In some of the cases, it is worth nothing, the Haredi networks did not even bother to deny the allegations.

Although every single ultra-Orthodox education network has been sued, this article focuses on the two biggest: the umbrella organization for the Lithuanian and Hasidic institutions, known as Independent Education, and the Bnei Yosef network, which is affiliated to Shas. Together, they cater for around 63 percent of all ultra-Orthodox students from elementary school to middle school (around 130,000 and 50,000 respectively) and, according to estimates, they employ a total of 17,500 teachers.

Despite repeated requests, neither of the networks agreed to respond to this article. More surprising, however, was the silence of the regulatory body responsible for overseeing the transfer of these substantial sums to the networks. The Ministry of Education stated that the matter falls under the jurisdiction of the Ministry of Finance, which declined to comment.

The regulatory body responsible for overseeing the transfer of these substantial sums to the networks, did not respond. The Ministry of Education stated that the matter falls under the jurisdiction of the Ministry of Finance, which declined to comment.

Bnei Yosef |

Teachers are responsible for repaying the network’s loans

Most of the students enrolled in the Bnei Yosef network attend schools which have adopted what is known as the “Sephardi stream” of education; a minority of the schools in the network belong to Ashkenazi Hasidic sects that, for whatever reason, chose to operate under Bnei Yosef’s administrative umbrella. The annual budget for the network is around 1.2 billion shekels ($360M), the vast majority of which (around 900 million shekels; $273M) comes from the Ministry of Education. Since the network includes the core subjects in its curriculum – and notwithstanding questions that have been asked about the standard and extent that these subjects are taught – the funds transferred to the network are defined in professional jargon as “100 percent.” That is, they are identical to the funds that the government gives the state-run education system.

Several lawsuits have been filed against Bnei Yosef over the years by former employees, but none of them managed to open the same Pandora’s box that the class action suit filed by Avner – his name, like all of the people interviewed for this article, has been held back – a former teacher who claims that the network refused to pay him for non-classroom activities.

A little background: every teacher in Israel is entitled to three paid hours a week that they can use for non-frontal assignments, such as preparing students’ homework, grading exams and so on. The class action suit alleges that Bnei Yosef did not pay its teachers this sum, which comes out to around 70 shekels an hour ($21). According to the lawsuits’ calculations, the total sum that should have been paid to the network’s 3,500 teachers over a seven-year period comes out to more than 250 million shekels ($75.5M). The plaintiffs allege that while the Ministry of Education transferred this money to Bnei Yosef, they did not see a Shekel of it.

Avner, the named plaintiff in the suit, says that he was adamant to sue Bnei Yosef despite him and his being put under intense pressure beforehand and subjected to abuse afterwards. He also says that his daughter, who studies in one of the network’s schools, has been singled out for harsh treatment. At the time that he filed the lawsuit, he was still employed by Bnei Yosef – but was fired shortly thereafter.

“As far as I am aware, nobody at any of Bnei Yosef’s schools gets paid educator hours – but none of the other teachers are willing to speak out. They’re afraid. In the school where I taught, no one got that payment and I have friends in schools across the country – and I know for sure none of them got it either,” he tells Shomrim.

In its response to the lawsuit, Bnei Yosef rejected the allegation that none of the teachers were paid educator hours, but, in the same breath, admitted that not all of them did. Why? According to the network, some of the money did not reach teachers because the classes they taught did not meet the student-to-teacher ratio requirements, which meant that it did not have enough money to pay all the teachers. In other words: the network, which, as already mentioned, is funded exactly like the state-run education system, confirmed that it ignores Education Ministry instructions when it comes to class size. This, by the way, did not prevent Bnei Yosef from later adding to its response to the lawsuit that it does not get enough funding to pay for all the hours it needs while paradoxically claiming that unused educator hours are “returned” to the treasury.

Either way, that was nothing more than the opening salvo. In response to the specific case of Avner, Bnei Yosef claimed that he forged the certificates testifying to how many years he had been a teacher – which would have had an impact on his salary – even though the same allegedly fake documents, which it says prove its argument, are actually signed by the principal of the school.

During his testimony, Avner was asked to present his pay slips for the years in question and replied that he did not have them. Why? He told the court that there was a long and exhausting period of time when his salary was withheld. He said that he begged to be paid. “After several months,” he tells Shomrim, “I was paid under the table. The principal came all the way from Beit She’an to Tiberias. We sat together at the tomb of Rabbi Meir Ba’al Haness and he paid me in cash for the months I worked.”

Being paid in cash by an education network that is, on paper at least, funded by the state, might sound a little strange, but it turns out that Avner’s was not an isolated or even unusual case. Shomrim has obtained a Ministry of Finance document from 2022 which shows that regulatory authorities were aware of this practice. In the document, a senior treasury official claims that the Bnei Yosef network opens schools without advanced permission from the Education Ministry and then asks for retroactive approval – and also pays the teachers who worked there retroactively. According to the document, at the start of one school year, no fewer than one quarter of the network’s schools – around 60 of them – began teaching without the requisite permits.

The document analyzes the problematic nature of these practices in several contexts and also asks who actually pays the teachers’ salary. According to the same senior treasury official, they are anonymous non-profit associations that act as middlemen by paying teachers’ salaries until money arrives from the Ministry of Education. Sometimes, that can be as long as a whole year. According to the document, as soon as the approval and retroactive payment arrived from the Ministry of Education, the teachers were also given pay slips. This does not mean, of course, that they are paid twice. According to Avner, the teachers are then required to return the money they were paid to the nonprofits that covered their wages.

Payment in cash is also mentioned in another lawsuit filed against Bnei Yosef by an employee of one of the ultra-Orthodox institutions that the network operates. According to the details of the suit, teachers at the school were paid a certain sum, part of which they were required to “repay” to the school in cash every month. The plaintiff claims that teachers were even given detailed records of the sums they were required to repay. In its statement of defense, Bnei Yosef denied the allegations.

Back to Avner’s class action suit: Bnei Yosef also claimed in its statement of defense that Avner often missed the start of the school day. While this may sound like a complaint that an employee might legitimately make against an employee, it turns out that this is an issue within the ultra-Orthodox education system related to “prayer hour,” which has been the subject of several lawsuits in the past. Teachers in these networks are required to arrive at school early in order to be with their students during morning prayers – but they are not paid for their time. “The principal told me that I was arriving late, at 8:05 or 8:10,” Avner says. “I asked him what he meant by that. I’m early. I’m paid from 8:30, so if I arrive at 8:10 I’m actually 20 minutes early.”

“After several months,” Avner tells Shomrim, “I was paid under the table. The principal came all the way from Beit She’an to Tiberias. We sat together at the tomb of Rabbi Meir Ba’al Haness and he paid me in cash for the months I worked.”

Independent Education |

‘For six years, I didn’t have any rights’

Like Bnei Yosef, the Independent Education network is also 100 percent funded by the state, thanks to the fact that it teaches core subjects. But, like Bnei Yosef, there have also been reports that the level of teaching leaves a lot to be desired.

According to Miftach HaTaktsiv (a website run by the Public Knowledge Workshop that makes government budget data accessible to the public), the network’s budget in 2025 was 1.64 billion shekels ($497M), which funded the operation of approximately 240 schools. The figures do not make it clear whether this is the network’s total budget or merely what it gets from the state – and there is no other data available. The network also has a massive budget deficit of around 400 million shekels ($120M). In a series of court actions launched over the past few years by entrepreneur Israel Kroizer – a private citizen who decided to take action – it became apparent that the Independent Education network doesn’t care too much about its massive deficit and is counting on the state to bail it out. Without going too deep into the details, it would appear that the network’s faith is well placed. Incidentally, despite the deficit and other improper conduct, the network was given a certificate of good management from the Justice Ministry, without which it would not be eligible to receive any state funding.

The suits filed against Independent Education – the individual cases and the class action suits – also shine a light on a whole host of other allegations, all of which have a similar theme: they received only partial payment for rights and funds legally owed to them. One prominent issue that the lawsuits brought to the fore was that of substitute teachers – female educators who were employed for years on temporary contracts, even though the law stipulates that a substitute teacher can work no more than 51 days a year.

“Every year they fired me again,” says Na’ama, who was employed as a classroom educator. “For six years, I did not have any rights as an employee.” Na’ama was very concerned about even talking to Shomrim and did so only after repeated assurance that her real name would be withheld. At one point during the interview, she is joined by her husband. “It’s all very scary here,” she explains.

“It’s not like she taught every day in a different classroom,” her husband adds. “She had a regular class and they even told her in advance, ‘Next year, you’re supposed to be preparing material for first grade.’ Then they would fire her and reemploy her.”

In its response to the plaintiffs’ request to turn the case into a class action suit, the network did not deny that the plaintiffs were employed as substitute teachers, but argued that the regulations on the matter in the state-run education system do not apply to Independent Education and that it is under no obligation to pay them the money they are claiming. Independent Education went even further and claimed that if the substitute teachers had been paid as full-time employees, or as substitutes in accordance with the Ministry of Education’s regulation, they would actually have received less money.

Attorney Pini Kalman, who is familiar with and has filed previous lawsuits related to the issue, explains that the background to the chicanery with substitute teachers is that many women in ultra-Orthodox society study teaching. “At seminary, they were all forced to study teaching and there is a massive surplus of female teachers,” he says. “For every available position, there are 20 women willing to work.”

And when supply is greater than demand, there is exploitation. Substitute teachers, who are supposed to work for short periods, do not get social benefits, are not entitled to job security, do not accrue benefits for each year they work and do not get sabbaticals. “We had one plaintiff who worked at a school for five years as a regular teacher but was employed as a substitute. Her salary was close to minimum wage,” Kalman says.

Na’ama also tells Shomrim that there were other issues which convinced her to file a lawsuit. “Prayer hour, for example. I am required to spend half an hour with the girls every morning, but I don’t get paid for it. I don’t even get a lunch break. There’s no pension fund and no advanced study fund. I don’t get anything.”

Why, then, do the ultra-Orthodox education networks employ Haredi women as substitute teachers? According to Kalman, in cases where the school is funded by the Ministry of Education , this system allows them to benefit from the gap between the salary that they get from the state and what they pay their teachers. He explains that there is additional motivation – such as employing a teacher for very little money for a class that has not been approved (for example, because it contains too few students) and not budgeted for. Another reason, he says, is that the high birthrate in ultra-Orthodox society means that a large proportion of the personnel at any given school will be on maternity leave. Here, too, he says, there is a financial benefit to the networks.

Despite the deficit and other improper conduct, the Independent Education network was given a certificate of good management from the Justice Ministry, without which it would not be eligible to receive any state funding.

A prevalent culture

An analysis of the lawsuits shows that, while the culture of chicanery is prevalent, there has been a move in the right direction. In light of the increasing demand in ultra-Orthodox society for state-run Haredi schools, alongside legal and media pressure, the heads of the independent education networks are starting to recognize that change is needed. For example, a senior official from Independent Education, when asked about the network’s conduct, replied that the media persecutes the ultra-Orthodox education system but, in the same breath, said that the network was working, he claimed in cooperation with the Ministry of Finance, to introduce a computerized system to bring some order to some of the issues mentioned in this article. How the network operated until today – and why the treasury permitted it to act in this way – remains an unanswered question. It should be noted that, despite this move in the right direction, none of the people interviewed for this article was willing to say when, if ever, the results would be evident on the ground.

Israel Kroizer agrees that most of the decision makers, including the regulators, are now convinced that the system cannot continue like this over time.

Kroizer, a 72-year-old engineer and entrepreneur, launched his private campaign out of anger at the financial exploitation while Israel was fighting a war. “What astonished me is that the ultra-Orthodox were only interested in money,” he says. “The open faucet was pouring endless money into their coffers.”

Kroizer is waging his legal battle alongside his son, Or, a former high-tech executive whose second career is as an academic. Together, they dove into the financial records of the associations which run the education networks. “You’ve got all the information there,” says the father. “The reports suggest that, despite everything, these associations are on the verge of collapse.” His son adds: “They are convinced that they are not associations; they get everything from the state. That is really the situation, because the establishment played ball.”

Journalist and academic Dov Elbaum argues that the conduct of these ultra-Orthodox educational networks comes from a different place. “The state is considered an external regime and the moment that is the case, laws against theft and embezzlement no longer exist. There are even those who believe that it is a mitzvah, because otherwise the government would use the money for what they call ‘impure and blasphemous’ events. They are using the money to nourishultra-Orthodox families.”

Elbaum adds that this approach is also evident in the gap between the legally mandated salary the networks are obligated to pay their teachers and what Haredi teachers actually earn. “If they told the teachers in advance what their salary was and that was the final word, then, as far as they are concerned, they have closed a deal with the teachers. They do not feel in any way obligated by the fact that the state ruled that teachers must be paid more.”