War on Attrition: Tens of Thousands of Children Could Become ‘Hidden Dropouts’ – and the Education Ministry Has No Data

The State Comptroller issued a dire caution, professionals in the field waved warning flags and MKs demanded answers. But the Education Ministry insists that high-school attrition is waning. Where does the discrepancy come from? The ministry is not considering the ramifications of the coronavirus pandemic or hidden dropouts – children and youths who are registered at school in name alone. A special Shomrim report looks at the root causes of attrition, which is threatening the futures of tens of thousands of Israeli children and youths.

.jpg)

.jpg)

The State Comptroller issued a dire caution, professionals in the field waved warning flags and MKs demanded answers. But the Education Ministry insists that high-school attrition is waning. Where does the discrepancy come from? The ministry is not considering the ramifications of the coronavirus pandemic or hidden dropouts – children and youths who are registered at school in name alone. A special Shomrim report looks at the root causes of attrition, which is threatening the futures of tens of thousands of Israeli children and youths.

.jpg)

The State Comptroller issued a dire caution, professionals in the field waved warning flags and MKs demanded answers. But the Education Ministry insists that high-school attrition is waning. Where does the discrepancy come from? The ministry is not considering the ramifications of the coronavirus pandemic or hidden dropouts – children and youths who are registered at school in name alone. A special Shomrim report looks at the root causes of attrition, which is threatening the futures of tens of thousands of Israeli children and youths.

Photo Illustration: Shutterstock

Chen Shalita

August 15, 2022

Summary

Listen to a Dynamic Summary of the Article

Created using NotebookLM AI tool

W

hat happens when a young boy or girl decides they do not want to study in high school anymore? They cut a lot of classes, they turn up late and even when they are in the classroom, they are not really present. When does the school realize there is a problem and this is not a case of occasional class-cutting? And when it does recognize the extent of the crisis, is the school capable of dealing with that student – or does it simply give up? Does it fight to keep the student in school, or does it wait for a different educational framework to relieve it of the burden? When does the education system spring into action to prevent students from dropping out entirely, and what does it really do?

Let’s start with the numbers. A report published two months ago by the Knesset’s Research and Information Center paints an ostensibly optimistic picture: since 2010, there has been a steady decline in the overt dropout rate from secondary education in Israel. This relates to the number of students who officially leave school and are no longer registered as students in any educational institution, as opposed to the hidden dropout rate, where the student is present in class but not taking part. When hidden dropout is not addressed, it leads, in most cases, to overt dropout.

According to the report, 9,583 students in seventh to twelfth grade dropped out of school under the supervision of the Education Ministry in 2020, which is 1.2 percent of students that age. This appears to show progress since, in 2010, the dropout rate was 2 percent – or 13,382 students. However, according to the Research and Information Center, these figures are not an accurate representation of the truth since, in 2019 and 2020, there was no regular in-person teaching in the Israeli education system because of the coronavirus pandemic. A large part of the academic year took place on Zoom and since schools were already struggling with Zoom attendance and getting students to turn on their cameras, they did not keep attendance records of who was there – and certainly did not look to exclude students for nonattendance or disciplinary problems, as happens during normal school years.

So, what was the point of all this, if the student did not attend Zoom classes, barely showed up at school for those months when there was in-person teaching and just floated through the year without engaging in significant learning? Good question.

A report by the State Comptroller into remote teaching and learning during the pandemic slammed the Education Ministry for burying its head in the sand and not bothering to collect data that would accurately reflect the true situation. “Researchers in Israel and worldwide,” the report stated, “estimate that the dropout phenomenon is likely to worsen in the wake of the Covid-19 pandemic and the shift to distance learning. It will also appear in populations not previously defined as at risk for student dropout. Nevertheless, the Education Ministry did not collect the schools’ monitoring data on students’ attendance and active participation in distance learning lessons. It lacked complete data for the entire education system on hidden dropouts and students who ceased contact with their schools during the Covid-19 pandemic and the year preceding it.”

Even now, a year after the publication of that report, there is still no index to gauge the extent of hidden dropouts, even though the Education Ministry told the State Comptroller and the Knesset’s Education Committee at the time that it was working on it – and that it has even set up a pilot scheme based on two schools. This did not win over MK Ya’akov Margi (Shas). “When you wanted more information on the potential of those students studying advanced math and physics, you managed to get nationwide data from schools within two weeks,” he rebuked the Education Ministry representative at a meeting in December 2021, “but getting to the bottom of hidden dropouts isn’t urgent for you.”

How complicated can it be to create a statistical database of this kind since, in any case, schools already input this information on an hourly basis? Any parent with a child in the Israeli educational system can log on to one of the dedicated websites, like Mashov, and see which classes their child attended, whether they brought all of the required equipment, was written up for misbehaving, or arrived late. The computerized information already exists, so why is the Education Ministry dragging its feet?

“It’s true that it would be a more complex index than that for the overt dropout rate, but there are enough experts in the Education Ministry who are qualified to develop it,” say sources well versed in the issue. “It’s unclear why the ministry is presenting a positive picture when the situation is not good. If they were to make the real figures available, they could ask for extra funding to address the problem. It appears that there are power struggles going on there, perhaps even political considerations.”

The Education Ministry gave the following response to Shomrim’s questions: “The Education Ministry has defined tackling the problem of dropouts as its key goal. Because of this, the dropout rate has fallen over the years. During the coronavirus pandemic, there was an increase in the hidden dropout rate. Still, thanks to a policy implemented by Education Minister Dr. Yifat Shasha-Biton, who instructed the education system to remain open, the hidden dropout rate has fallen. When she was appointed to the position, the minister ordered the development of a tool for measuring the hidden dropout rate. The ministry is working at this time to develop and certify this tool.”

On what basis have you decided that there’s been a decline in the hidden dropout rate if you have no tool for measuring it? Where are the statistics?

“We relied at the time on reports from principals who identified a decline.”

What figures did these principals report?

“We do not have the figures at hand.”

So, how did you decide that there’s been a decline if you don’t have the figures?

At this point, the Education Ministry stopped responding to Shomrim’s questions.

%20(1)%20(1).jpg)

“When you wanted more information on the potential of those students studying advanced math and physics, you managed to get nationwide data from schools within two weeks,” MK Ya’akov Margi rebuked the Education Ministry representative, “but getting to the bottom of hidden dropouts isn’t urgent for you.”

90,000 Students Under Supervision

From where, then, can one get an indication as to the extent of the hidden dropout phenomenon? From the truancy officers, also known as attendance officers, who are the first people that schools contact when they identify a student in danger of dropping out. The Education Ministry’s Truancy and Dropout Prevention Department operates within the framework of the Compulsory Education Law and is responsible for implementing it. To this end, it has a network of truancy officers working with each local authority.

In 2019, truancy officers dealt with 82,000 students – around 4.6 percent of the total number of students – and in 2021, that number jumped to 90,000 (about 5.7 percent). Eight thousand additional students in two years, and these are just those whose cases were reported by the schools and transferred to the truancy officers.

Although the Compulsory Education Law, which applies to children aged between 3 and 18, obligated schools to report any student who is absent without justification for seven consecutive days or for 14 days in total, in practice, it does not work like that. The lack of staffing – 732 truancy officers for 90,000 students – creates a situation where the officers must prioritize cases. If the case is not obviously urgent and severe, the officers’ involvement begins at a later stage. “There are written instructions and then there are verbal instructions,” explains one person involved in the process, “so we use the probability test and common sense. Any student viewed as a ‘good kid’ is left alone if they didn’t bring in a sick note or went on a family vacation in the middle of the school year. No one wants to bring out the big guns in such cases.”

“In recent years, we have focused mainly on prevention, that is, on hidden attrition,” Maor Tzemach, the chair of the truancy officers’ union, told Shomrim. “Schools are a social place, so most students still attend. Even if it’s only to meet friends or to arrange to meet up later. Our working assumption is that if we don’t deal with hidden dropouts, it will become overt.”

A., who is now 18 years old, managed to turn himself around thanks to his mother, who did not let up, and a truancy officer who he describes as “amazing.” According to A., Tzemach, who was the officer handling his case, “showed that he cared.” In the end, as many of the students interviewed for this article testified, all children need is one adult to believe in them. And that, if possible, there is the budget to back up that belief. “I attended a lot of different schools until I enrolled in one school that recognized that I am a human being – and I blossomed and graduated there,” A. tells Shomrim. “Until then, I met a lot of school staff who spat in my face. None of them came out and told me I would never amount to anything. And none of the schools expelled me because I wasn’t a disruption, I just didn’t attend classes. I was one of those kids that sometimes comes to school but doesn’t go into classes. Sometimes they try to study a little. Sometimes they don’t attend at all, depending on their mood. In seventh and eighth grade, I knew all of the corridor kids. I went to school to see friends and for the atmosphere.”

Did no one call you out?

“I was called the secretary’s office, I had conversations with the principal, but as long as I was getting good grades, no one really cared. When I didn’t turn up for two weeks, the homeroom teacher didn’t even bother to send my parents a message. The school just wants a quiet classroom, and for the school’s average grade to be high. I didn’t feel like they saw the students themselves.”

S., now 23, dropped out of high school at the age of 17 and her primarily memory is one of mutual incompatibility. “I never felt that I was suited to school. I was good at music and art, I dressed strangely, and I didn’t get along socially. And when my best friend got cancer in 11th grade, I took it as a sign to drop out. I took a course at the Rimon School of Music, played in bars, and made money.”

And the education system just allowed that to happen?

“My parents split up when I was eight years old and I moved from city to city and attended seven different schools, so maybe that’s why I fell through the cracks. If primary and secondary school teachers had invested more in me, I might not have wanted to drop out of high school. They occasionally tried to encourage me. One truancy officer who was assigned to me in high school would call me in the morning to ask if I was awake. I answered, ‘Yes, but I’m not going to school.’ That pissed her off, but it didn’t make me go to school.”

What did your parents say?

“They wanted me to graduate, but they believed I would be okay whatever happened. Even today, I don’t see any need for a high-school diploma. I’m 23 years old and I’m about to get married. My fiancé and I have a very successful production company.”

%20(1).jpg)

S., now 23, dropped out of high school at the age of 17: “My parents split up when I was eight years old and I moved from city to city and attended seven different schools, so maybe that’s why I fell through the cracks. If primary and secondary school teachers had invested more in me, I might not have wanted to drop out of high school".

One officer for 123 at-risk kids

As mentioned, there are 732 truancy officers across Israel to deal with around 90,000 children – and everyone agrees this is not enough. MK Orit Strock (Religious Zionism), who has been campaigning in parliament to improve the working conditions of truancy officers, told Shomrim that “the Education Ministry is responsible for covering 75 percent of the truancy officers’ salaries and for giving them professional and pedagogical training; the local authority is their direct employer and pays the rest of their salaries. The moment two bodies share the position, no one takes full responsibility for the situation, and that’s clear. Their monthly salaries are pitiful, around 6,000 shekels (around $1,800) after tax for a new officer and that doesn’t go up significantly with the years. There is a high turnover of truancy officers and sometimes, the positions are filled by unqualified people because that’s all there is. A good truancy officer can do wonders and should be rewarded accordingly.”

.jpg)

Since 2017, 293 truancy officers have left the system to be replaced by 273 new officers – even though it is evident that the original number was woefully inadequate. By law, a truancy officer must have three years of teaching experience, assuming that prior knowledge of the school system will help them do their job. “The problem is that the salary of a truancy officer is a step-down, even compared to a teacher in primary school,” says Tzemach. “A teacher who becomes a truancy officer is automatically taking a 30 percent pay cut because we are paid according to the pay scale of the Complementary Education Organization and it’s a 24-hour-a-day job. On one occasion, I had to take a student home at two o’clock in the morning.”

David Attias, a truancy officer for the Jerusalem Municipality’s Education Authority, adds: “I deal with 160 children and that’s a hell of a challenge. They are all in some kind of danger of dropping out. During the pandemic, the numbers here skyrocketed. And, as a truancy officer, you have to prioritize. I deal with urgent cases at once, but some kids don’t shout out for help. The depressed, quiet one who also needs me. I have developed the ability to see everyone. Can I tell you that there are no kids who fall between the cracks? I’m sure that we are missing some children.”

Add to this, Attias says, “that we’re working at a massive technological disadvantage. The computerized system that the Education Ministry set up is terribly old-fashioned and isn’t synchronized with computers in schools, so I have no way of getting alerts about the situation.”

So, how do you know when there’s a problem?

“I turn up at the school in person to talk with the teachers. Every homeroom teacher knows their students and whether a student is genuinely sick or pretending. At more challenging schools with a dropout problem, I visit at least two or three times a week. As soon as I step into the teachers’ room, there’s a line of teachers waiting to talk to me.”

Shira Polack, the head of the truancy officer department in Ofakim, is the main officer handling ultra-Orthodox girls and special education. She is still dealing with attendance records in cardboard folders. “For the most part, the ultra-Orthodox education system is not computerized,” she explains. “By law, I am entitled to walk into a classroom and inspect the attendance register. At the same time, there are meetings with the advisor. These meetings are important because one sees doubts that one wouldn’t see in a register or on a computer. For example, whether there is a legal obligation for a teacher to report something that they overheard. Or how to handle the girl who comes to school but excuses herself to go the restroom and doesn’t return. Is that considered truancy?”

When each truancy officer deals with an average of 120 students, how many are actually being helped?

“Twenty percent of the students get intensive help and we ask the schools for daily reports about them. For the other 80 percent, it’s more a case of follow-up. Some students go through a brief period of distress and sometimes all it takes is a mediation meeting, opening up some blockage, and the student gets back on track.”

Polack, too, is unhappy with truancy officers’ terms of employment, which make everything even harder. “Sometimes people quit after two paychecks,” she says. “I just recruited a new truancy officer, a father with a large family. He earns less than 7,000 shekels a month. It’s embarrassing. I just pray that he doesn’t quit because he’s excellent and he really knows how to talk to the children.”

The Education Ministry said in response that “given the importance of the holy work that the truancy officers do and their huge contribution, the Education Ministry is working with the Finance Ministry to increase the number of officers employed.”

‘Every Parent Wants Their Child to Study”

How does the process work? The school is supposed to be the first to identify a problem, the expectation being that it tried to deal with it within the school as part of what is referred to as a policy of containment. The adviser is then brought into the picture, the parents are contacted and the student is called for a wake-up talk. “We ask how come the student always has a stomachache on Fridays, we try to understand what’s going on, where help is needed and we explain to the parents that they are responsible,” says Zohar Margalit, head of the Empowerment Unit at Tel Aviv Municipality’s Youth and Child Development Department.

Are the parents surprised to hear that their child has not been attending school?

“Parents of high schoolers mostly know, but they don’t have the energy to fight. They have a problem with parental authority and they tend to give up. In elementary school, it’s more a case of parental dysfunction because when a child of that age doesn’t go to school, it means that the parents didn’t wake up in time in the morning, that they don’t organize their child’s backpack and don’t drive them to school.”

When the school is not satisfied by the answers given by the parents and the students, it is supposed to find the resources to help that student within the school. Resources like academic assistance, extra teaching hours through programs like New Horizon and Oz Latmura, and psychological support through the Education Ministry’s advisory teams. At this stage, and once the parents have given their consent, the truancy officer who works with the school is brought into the picture.

“Every parent wants their child to study,” Attias says. “I’ve yet to encounter parents who say, ‘Leave us alone, let the kid do what he wants.’ In many cases, the parents are incapable of influencing their child and are grateful for our help. We are a kind of emergency room for cases the school doesn’t know how to handle. When it comes to students using alcohol and drugs, the Adolescent Unit gets involved. In very complex cases, we also bring in the Welfare Department. There are sometimes when I have made a home visit and thought to myself, ‘Wow, I wouldn’t want to go to school either if I was in the child’s position.’ I have seen the worst kind of neglect, which doesn’t allow anything positive to develop. And then you try to get the student out of that environment, to a boarding school, for example.”

“I am the student’s advocate,” Polack adds, “so I ask to hear their side of the story. That exposes us to information the school hasn’t told us – like maybe there’s hostility between a student and a certain teacher. And then we act as mediators, or we consider moving the student to a different school. When a student does not attend classes, that’s always just the tip of a more serious iceberg. Sometimes the problem is not with the school, but with the family, and we have also encountered parental alienation.”

Do the parents cooperate?

“We invite them to attend an orderly meeting at our offices at a time that’s convenient for them and if they don’t show up, and I call them dozens of times without getting a response, I’ll simply go and knock on their door. And if they don’t answer, I’ll speak with a neighbor. One time, I was told that the family had disappeared somewhere in the middle of the night because the father had got into trouble with the black market. We hear about divorces when one of the parents moves with the child without a court order. Sometimes, we turn up in places that the welfare services are unaware of and it’s only because of the child’s truancy that we discover the problem. And there are children who, when I turn up there, I find out that the welfare services are very well acquainted with the whole extended family.”

Have you ever been alerted to a potential dropout by someone other than the school?

“Yes, sometimes the family or the child will come to my office; sometimes a neighbor reports that the child is wandering around during school hours. We meet children with whom we’ve never had problems in the past, and they’re having a challenging time returning to school after the pandemic. The coronavirus did ongoing damage, the children have not gone through vital stages of social and learning development.”

Hodiyah Yahav, director of the Classrooms for Dropout Prevention run by the Menifa NGO, says that “because of the Zoom teaching during the pandemic, youngsters realized that they don’t need to study for eight hours a day and they have left normative schools for more alternative frameworks. During the pandemic, students weren’t excluded from disciplinary problems because there were no lessons. They weren’t excluded for absenteeism because they weren’t on Zoom. Later on, we paid a price for this. Girls have told me that they disappeared during the pandemic and no one notices – and then no one noticed when they didn’t return.”

“I wish the education system would respond as compelled by law and that the truancy officer would call me after a week. That way, I wouldn’t have any work to do. But the system is worn out.”

.jpg)

Hodiyah Yahav, director of the Classrooms for Dropout Prevention run by the Menifa NGO, says that “because of the Zoom teaching during the pandemic, youngsters realized that they don’t need to study for eight hours a day and they have left normative schools for more alternative frameworks. Girls have told me that they disappeared during the pandemic and no one notices.”

‘They Tested Me at First and Called Me Teacher’

Tel Aviv Municipality offers the most creative solution to the high-school attrition problem, which has employed counselors known as ‘prevention guides.’ For the most part, they are people in their late 20s who have a background not only in youth development but also have an academic background in education and caregiving. They work closely with students who are in danger of dropping out. “One truancy officer for every 120 students cannot engage in preemptive intervention,” says Margalit. “In contrast, a counselor who is affiliated to a school can look after the 15 most complex cases that we meet there. They talk to them, call them in the morning to ask if they’re going to school and sometimes even pick them up from home.

“These programs are highly successful because the kids feel like they’re being seen. Children who forge a significant connection manage to drag themselves to school because they want to see their counselor. Even if they start by turning up to school just for that, and the next day they attend one class, it’s a start. And, over time, the child will build up some resilience, so even if they don’t graduate with a full matriculation, they won’t feel like a failure, and they won’t feel targeted. These are the feelings we hope to change.”

What about those students who don’t show up at all?

“During the pandemic, the number of kids who dropped out of school – and of life in general – because of depression and anxiety skyrocketed. The Education Ministry allocates teachers who will visit their homes. There are some kids on the margins who mainly need emotional support.”

Ruth Okashi, who has degrees in education and criminal rehabilitation, is a prevention guide at a high school in Jaffa, where she worked with 18 students last year. “To start with, I sat on the benches during the breaks and just observed,” she says. “After that, I tried to woo them using the things that interest them and now I hang out with them freely. They all have one regular hour with me and know I am available if they need me. I have an office with treats, some food and snacks, where they can come. It softens the school experience for them and creates a sense of belonging.”

How do you mediate between them and the school?

“The school has a treatment center. And some of the kids felt threatened by it and resisted the idea of being diagnosed, so I went with them. If the kids let me, I’ll talk to the teacher about them. There are some who I call every day to ask if they’re coming to school because that’s what they need from me – to show them that I am taking an interest in them. But I’m not a cop and don’t demand that they attend classes. During the pandemic and the summer vacation, I met them in their homes. That’s important if I want the family to be involved.”

Are you not perceived as part of the system?

“At first, they tested me, called me teacher, but now there’s no confusion. They understand that I am not their friend but also not really part of the system. They know that there are some things that I would have to report them for.”

Tel Aviv Municipality pays the salaries of four truancy officers without any contribution from the Education Ministry. “We realized that if we counted on the Education Ministry alone, we wouldn’t be able to deal with the students in our city,” says Margalit. “Even so, a truancy officer in Tel Aviv has between 120 and 140 students in his or her care.” Does this policy violate the principle of equality, or is it merely the legitimate priority of a local authority? What’s certain is that more affluent authorities have more resources to deal with youth attrition.

Do Dropouts Become Criminals?

“When the school gives up on a child, it usually sends him or her into a downward spiral,” according to educational experts. “The more students move between schools, the greater the chances of dropping out. Sometimes, the system says that it’s better for one child to drop out than for an entire class. That usually happens when the parents of the other students put pressure on the school to exclude the ‘disruptive influence.’ Parents want a sterile classroom, but that is not the kind of classroom that helps narrow the gaps.”

Polack knows this first-hand. “The role of schools goes far beyond just teaching. A child who is in a framework is a child who will behave differently in society. Studies show that there is a profound connection between children who drop out and a high criminality rate, teen pregnancy, drugs and other problems. The low active dropout rate in Israel is indeed considered a success, but it’s important to know that to achieve it, they lowered the teaching level of the child. They contained attrition by having lower standards. This has not contributed to equality of opportunity because not every child finishes at the same point. A child who graduates from a framework for youth development is not the same as a child who graduates from the Israel Air Force Technical College. It makes a difference if the child graduates with a diploma or not.”

“Attrition from formal studies,” according to last year’s report by the Knesset’s Research and Information Center, “is considered a key factor that feeds and perpetuates social gaps. The phenomenon of attrition has been linked to various dangerous behaviors. Youths who are not part of an educational framework are involved in crime at a much higher rate than youths who are. According to data from the Central Bureau of Statistics, in the 2019-2022 school year, the number of criminal cases opened against youths aged between 12 and 18 who were not in any educational framework was 4.5 times higher than youths who attended schools supervised by the Education Ministry (18 youth per 1,000, compared to 4, respectively).”

Prof. Mona Khoury-Kassabri from the Hebrew University’s School of Social Work and Social Welfare has been researching youth criminality and is less convinced about the connection between attrition and crime. “There’s no data showing that a high-school dropout will become a criminal. That’s like saying that attention deficit disorders cause criminality because most prisoners suffer from it. You can be a criminal even if you sit in every class to 12th grade. The most important criterion here is an academic horizon, and that’s a criterion that crosses sectors of society. A child who is not committed to studying, who cannot see a future and believes that it’s realistic that they will succeed in life is in greater danger of descending into crime.”

Are you referring to academic studies?

“No, not even to the question of grades, but to the fact that studies are important to him, to progress in life and to get a profession. A child who had someone in the school believe in them and who made them stretch themselves ended up with a graduation diploma.”

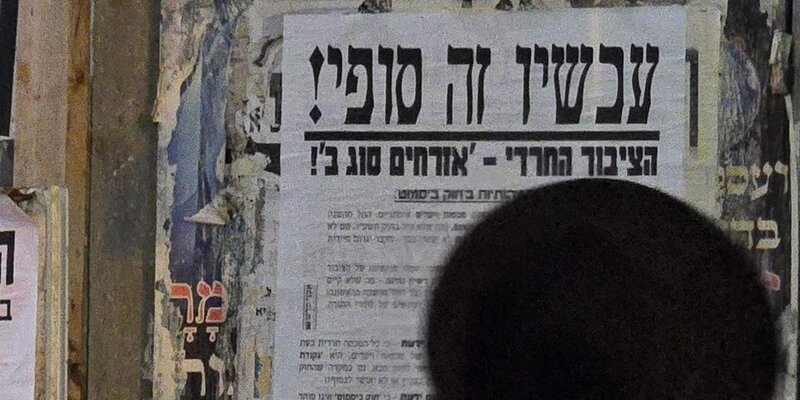

A Wave of Ultra-Orthodox Dropouts

“The Pandemic Accelerated the Process”

As mentioned above, the coronavirus pandemic created a lot of pressure on the system. Dr. Ruth Baruj-Kovarsky from the Brookdale Institute is currently working on a research paper into truancy officers in Israel during the pandemic. At the annual conference of truancy officers last year, she said that “the disconnect has been created, among other things, because of the technical difficulties of remote learning; some families do not have a computer or internet connection, and there was also confusion because of the changes to the patterns of study. Some local authorities managed to operate support networks and provide solutions in the form of equipment. Some took on volunteers to teach the students how to use Zoom, but not all of them could do so.”

Rabbi Eldad Tam, the director of the truancy department in Jerusalem Municipality’s ultra-Orthodox education division, which oversees some 1,300 students, says there has been a wave of attrition since the pandemic. “The coronavirus accelerated processes,” he says, “especially among students with learning difficulties and emotional problems and those who do not have strong family support. It happens most often during moves. The move from ‘little yeshiva’ [the equivalent of middle school] to a ‘big yeshiva’ [high school] and the move from a Talmud Torah [primary school] to a little yeshiva.”

Do they want to work? To join a secular framework?

“There are always those who want a secular education or less religious strictness – and this has increased in recent years because of exposure to the internet. But we’re mainly seeing kids who don’t want to do anything. They wander around the streets and are exposed to things that could lead them to crime.”

What are you doing to get them back into the classroom?

“We woo them. We talk to them about their future. Some boys have menial jobs because they want money here and now. We tell them, ‘Don’t make do with stacking shelves in the supermarket or delivering pizza. Study something.’ As an ultra-Orthodox Jew, I have unfortunately agreed with a young lad’s demand to attend a secular school because, as far as I am concerned, it’s better that he be a mensch and not wander the streets. Afterward, we’ll deal with his faith.”

Truancy officer David Attias from Jerusalem Municipality’s education administration adds: “I dealt with one child from a revered rabbinical family. When I visited the home, I saw massive neglect. It wasn’t conducive to studying. He told me that he wanted to learn in a secular school. At first, I told him there was no way, but when I saw how depressed he was and how he just sat at home for a year, I asked, ‘And what if I make it happen?’ He promised me he would finish high school and graduate with a diploma. It took me ages to convince the parents. I told them, ‘Put religion to one side for a moment and deal first of all with the boy’s soul.’ In the end, they agreed that he could go to a boarding school. When he was there, he sent me a copy of the certificate of excellence he received.”