Trial and Error: New Tax Could Cost Israeli Families Up to 1,800 Shekels a Month

A new tax – which the treasury claims will get rid of traffic jams – will cost Israelis 15 shekels a day to drive from Kfar Sava to Herzliya or 22.5 shekels from Ramle to Holon. It now turns out, however, that the Knesset approved the new tax based on inaccurate, problematic, and manipulated statistics. These included successful but unrealistic results from a pilot scheme that examined the effectiveness of the tax and a survey that allegedly proved that poor people do not travel to the center of Israel. So, where did the treasury get its data from? Mainly from Google Traffic. One transportation expert says that, at best, the impact on congestion will be marginal. A Shomrim investigation in cooperation with TheMarker

.jpg)

.jpg)

A new tax – which the treasury claims will get rid of traffic jams – will cost Israelis 15 shekels a day to drive from Kfar Sava to Herzliya or 22.5 shekels from Ramle to Holon. It now turns out, however, that the Knesset approved the new tax based on inaccurate, problematic, and manipulated statistics. These included successful but unrealistic results from a pilot scheme that examined the effectiveness of the tax and a survey that allegedly proved that poor people do not travel to the center of Israel. So, where did the treasury get its data from? Mainly from Google Traffic. One transportation expert says that, at best, the impact on congestion will be marginal. A Shomrim investigation in cooperation with TheMarker

.jpg)

A new tax – which the treasury claims will get rid of traffic jams – will cost Israelis 15 shekels a day to drive from Kfar Sava to Herzliya or 22.5 shekels from Ramle to Holon. It now turns out, however, that the Knesset approved the new tax based on inaccurate, problematic, and manipulated statistics. These included successful but unrealistic results from a pilot scheme that examined the effectiveness of the tax and a survey that allegedly proved that poor people do not travel to the center of Israel. So, where did the treasury get its data from? Mainly from Google Traffic. One transportation expert says that, at best, the impact on congestion will be marginal. A Shomrim investigation in cooperation with TheMarker

Photo: Bea Bar Kallos

Eyal Abrahami

June 10, 2022

Summary

Listen to a Dynamic Summary of the Article

Created using NotebookLM AI tool

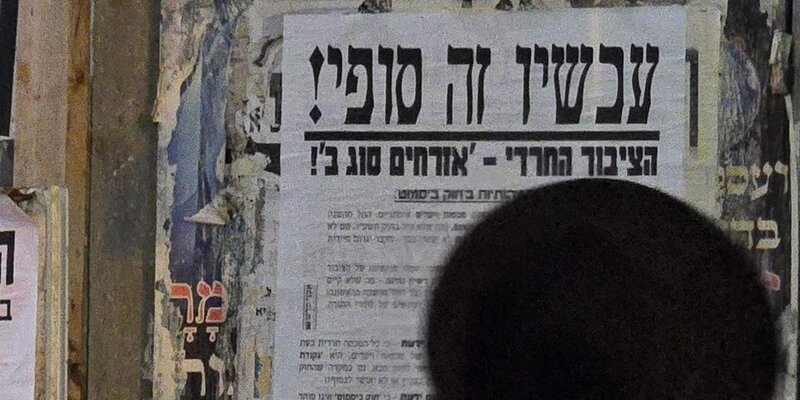

After a prolonged absence from the public discourse, the cost of living recently made a dramatic comeback, providing endless headlines for anyone inclined to publish them. The prime minister, for example, launched a program to help working families; the finance and economy ministers sent threatening letters to several companies; various Knesset committees held long and well-documented hearings; while analysts and studio panels produced countless words of wisdom about the rising prices of gas, pasta, and deodorant. Against this backdrop, therefore, it is hard to understand how the approval of the so-called congestion tax – perhaps the heaviest single tax that has been levied against Israelis since the mid-1980s – went below the radar.

The sums of money are barely believable: according to the most conservative and minimalizing estimate, a couple who works somewhere between Rishon Letzion and Ra'anana and who uses two cars will pay around 600 shekels a month under this new tax. If one or both of the couple happens to work in the heart of Tel Aviv, their monthly congestion bill could jump to 1,800 shekels – a sum that would cover the inflation on 2 tons of spaghetti and leave money over for a few cans of deodorant.

The level of tax is not the only problematic aspect of this new tax and the process by which it was approved. The findings of this investigation paint an embarrassing picture of the figures that the treasury provided to lawmakers at the discussions where the tax was approved. For example, representatives of the Finance Ministry and the Transportation Ministry presented Knesset members with information that can most generously be described as incorrect. The most egregious example was the way that the results of a transportation trial that was supposed to predict the impact of the tax, were presented. The trial, which was conducted at the same time as Israel was going through the first four waves of the coronavirus pandemic and the social unrest that they created, had not been completed when it was presented to lawmakers – and the ostensibly successful results that were presented as in no way similar to the outcome that has been reached since then.

Both ministries tried unsuccessfully for several months to conceal the real outcome of the trial from Shomrim, and they are revealed here for the first time. Based on the final results of the experiments, it seems that the new tax would have a marginal impact on congestion at best.

And this is only the beginning. The work of an academic panel that was supposed to examine, inter alia, the effectiveness of differentiated tax levels was halted before it even began. In another context, it was revealed that the State of Israel has no data on the amount of traffic in Gush Dan and that this new tax, from which the government hopes to raise huge sums of money, is based on data obtained from Google Traffic. Moreover, a survey was commissioned with no socio-economic element to it, which ostensibly proved that the tax would not affect Israel's weaker socio-economic sectors. It also included overseas data that was manipulated for use in Israel and, of course, a lot of familiar and empty promises about how an upgraded and effective public transportation system, including many more bus lines, a light railway, and so on, would be operational long before the new tax comes into effect.

At best, the Knesset members exposed to this information were skeptical, unlike many others. They wanted to know if the state would find thousands more bus drivers, given that there is a shortfall in that area today? The civil servants' response: We really don't know.