While Ultra-Orthodox Draft Crisis Grips Israel, The Ultra-Orthodox Street Remains Indifferent

How can an ultra-Orthodox family, whose sons are about to receive army draft notices — and could find themselves on the front lines within months — remain so unconcerned? According to researchers and experts, the primary explanation is that few within ultra-Orthodox society truly believe a significant draft will occur. Additional factors include the reassurances provided by anonymous hotlines run by unknown organizations, as well as ongoing efforts by certain Haredi communities to cooperate with the IDF in seeking alternative solutions. Some also point to a leadership vacuum that has hindered the community’s ability to recognize the severity of the situation. But what happens if, contrary to expectations, a compulsory draft is actually enforced? A special report by Shomrim.

How can an ultra-Orthodox family, whose sons are about to receive army draft notices — and could find themselves on the front lines within months — remain so unconcerned? According to researchers and experts, the primary explanation is that few within ultra-Orthodox society truly believe a significant draft will occur. Additional factors include the reassurances provided by anonymous hotlines run by unknown organizations, as well as ongoing efforts by certain Haredi communities to cooperate with the IDF in seeking alternative solutions. Some also point to a leadership vacuum that has hindered the community’s ability to recognize the severity of the situation. But what happens if, contrary to expectations, a compulsory draft is actually enforced? A special report by Shomrim.

How can an ultra-Orthodox family, whose sons are about to receive army draft notices — and could find themselves on the front lines within months — remain so unconcerned? According to researchers and experts, the primary explanation is that few within ultra-Orthodox society truly believe a significant draft will occur. Additional factors include the reassurances provided by anonymous hotlines run by unknown organizations, as well as ongoing efforts by certain Haredi communities to cooperate with the IDF in seeking alternative solutions. Some also point to a leadership vacuum that has hindered the community’s ability to recognize the severity of the situation. But what happens if, contrary to expectations, a compulsory draft is actually enforced? A special report by Shomrim.

Ultra-Orthodox protest against the draft, mostly attended by young men and with limited turnout. Photo: Reuters

Lir Spiriton

July 20, 2025

Summary

Listen to a Dynamic Summary of the Article

Created using NotebookLM AI tool

Over the past few months, the vexed issue of enlisting young ultra-Orthodox men into the IDF has dominated the Israeli agenda. Last week, the crisis reached a crescendo when the ultra-Orthodox parties quit the coalition, accompanied by a series of increasingly harsh comments from senior party officials. Paradoxically, this storm – which has been the talk of every Israeli citizen who serves in the military, which has dominated social media networks and the traditional media and which threatens to tear asunder long-standing political alliances – is passing over the heads of the very people who are most likely to be affected by its outcome: the general ultra-Orthodox public. Unlike the politicians elected to represent it, the Haredi street is utterly indifferent to the issue of the draft and even when asked directly what will happen if and when the law is passed, the response is most often a shrug of the shoulders. The handful of demonstrations held thus far have mainly been attended by young people – sparsely attended at that. That may change in the future, people say, but, in the meantime, it appears that the ultra-Orthodox public is far from agitated.

Chats with random passersby on the street of Bnei Brak only serve to confirm this sense of disinterest. “There are people who are handling the issue and we’re not afraid and we’re not letting it bother us at all,” says one woman in her 60s who Shomrim approached in a store selling baby clothes. “All of my grandchildren got call-up papers and they are not even thinking about it. We listen to the gdoilim [the rabbinical authorities] and they take care of things.”

We got a similar response from three draft-age youngsters sitting in the shade on a street corner. “Everything’ll be okay,” one of them says dismissively as his friends nod with barely disguised disinterest. Elsewhere in the city, we spoke to a young man called Yehoshua, who says that he is 26 years old and that he is expecting to receive a preliminary call-up order in the coming weeks. Nonetheless, he is almost blasé. “None of the people I know are even trying to deal with their individual call-up order because they know that the yeshivas themselves and the Council of Yeshivas are handling the issue. We don’t even talk about it. Yes, we hear about what’s happening but it’s not something that bothers us.”

Ultra-Orthodox media personality Benny Rabinovitz, agrees that the Haredi public is indifferent. “They’ve wallowed around in the subject so much that an apathy has developed. Yesterday, someone came up to me and asked what I think about it. I was genuinely surprised that someone was even taking an interest. As far as I can see, it isn’t a subject that’s discussed in synagogue or on the street. As they say in these parts: Everything will be fine – and even better.”

The main reason: ‘The Haredim don’t believe they’ll be drafted’

How can we explain the equanimity displayed by ultra-Orthodox families, some of whose sons are – ostensibly, at least – about to be drafted into the Israeli military and could find themselves on the front line within a matter of months? Researchers specializing in ultra-Orthodox society highlight several explanations, the most important of which and over which everyone agrees, is the almost universal belief among the Haredim that there will be no mandatory enlistment of yeshiva students – certainly not in significant numbers.

“There are two possible outcomes at the moment. The first is that they do not manage to pass the law and then the army has all the tools that already exist in terms of sanctions against yeshiva students – and that will not drastically alter the number of ultra-Orthodox recruits,” says Dr. Gilad Malach, a research fellow at Israel Democracy Institute who specializes in ultra-Orthodox society. The alternative, he says, is that the government manages to pass a law in the spirit of the Document of Principles – the draft that was circulated in the Knesset in recent weeks after being coordinated with the ultra-Orthodox parties but which came to nothing. “We know what that proposal contained and in the short term – the next year or two – it won’t lead to a jump in the number of Haredi recruits.”

Journalist, author and academic Dov Elbaum has a similar view of the ultra-Orthodox recruitment issue. “Anyone who believes that it is possible to draft a significant number of yeshiva students using gradual and careful steps is either a liar or naïve,” he says.

The tens of thousands of draft papers that the IDF says it is planning to send out before the end of July will, according to Elbaum, will be treated exactly as former Chief Rabbi Yitzhak Yosef once famously recommended – they’ll be thrown in the trash. “It’s clear to everyone that nobody is going to send military police into the yeshivas of Bnei Brak and Jerusalem to arrest draft dodgers. They’ll try to catch them when they try to leave the country or when they are driving in their cars. It will be a fringe phenomenon and won’t really change much.”

As something of an aside, both Elbaum and Malach were asked what would happen, in their opinion, if – against all these expectations – the army did make a sincere effort to recruit yeshiva students, including imposing personal sanctions against draft dodgers. Elbaum says that it would radically alter the response of the Haredi street. “The first thing we would see, I believe, would be a dramatic increase in the number of Haredim going to see a psychologist and getting a mental health exemption from military service. I can also envisage a situation whereby young men with relatives overseas leave Israel for a while. There will also be those who hide out in their communities, hoping to ride out the storm. Either way, I don’t believe that significant numbers of yeshiva students will be recruited this way. There may be a small increase, but that will not change the picture substantially. A mandatory draft would shatter a norm that has become deeply enrooted in Haredi society and is integrated into their lifestyle. I do not see how a law of this kind or any kind can change that quickly.”

Malach is cautious when talking about a scenario in which there is mass recruitment. “There is still the possibility that, in a year from now, say, a new government will be established without the ultra-Orthodox parties or that they will be a fifth wheel and there’ll be an even harsher law than the one currently on the table. If that were to happen, I believe there could be a jump in the number of ultra-Orthodox recruits, mainly those who study less, who are less observant and less connected to that community. And it’s also possible that Haredim who know that they will pay a heavy price will enlist anyway. I also believe that the initial impact will primarily be institutional – that some institutions will not survive. Institutions for dropouts, for example, or less well-off institutions.

“If that happens, the whole process of recruitment will create a process of Israelization, because anyone who joins the army can make independent decisions on other aspects of their lives, like studies and employment – and that can make a difference.”

Other explanations: Telephone ‘reassurers’ and quiet negotiations with the IDF

Another explanation for the apathy toward the subject stems from the sense of security and certainty instilled by some officials, who promise their communities that a solution will be found. The ultra-Orthodox public, it is worth noting as an aside, is less exposed to the outside world and is naturally more naïve and more likely to believe promises – like the ones offered to anyone who calls up one of the hotlines that have sprung up in their dozens to address the issue.

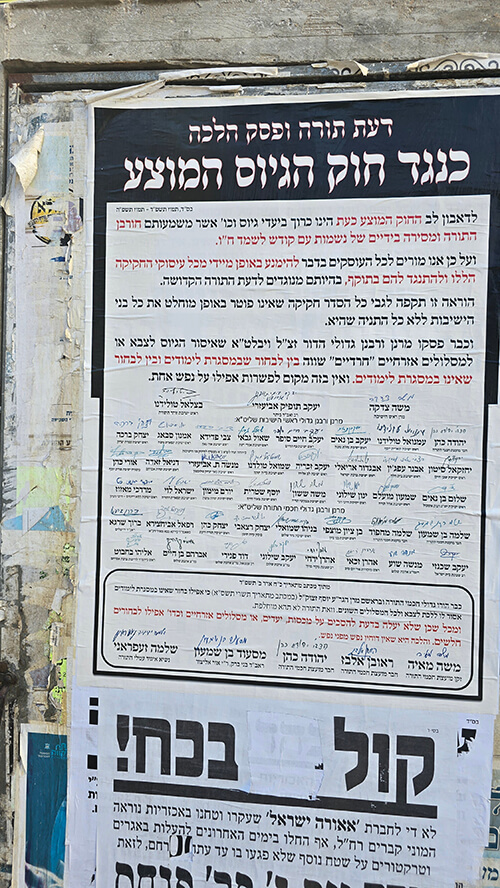

The telephone numbers of these hotlines can be found on every noticeboard in every ultra-Orthodox town and city, on pashkwolim (broadside posters festooning the streets of haredi Jewish neighborhoods) that promise to help any Haredi youth who has received a draft notice. “If you are one of the 89,380 yeshiva students, you’re not alone,” one of the pashkwolim declared in a large, bold font. “Got drafted? Call now!” another one reads. It is not clear who is operating their hotlines, but calling them opens up a window into a world of business centering on reassurances, promises and support.

The first stage of a conversation with one of these hotlines is dealing with the automated system which directs the call to the relevant department. Among the options offered are “Help and advice” and “General explanation.” Perhaps inspired by the public campaign launched by wives of Israeli reservists, the hotline also has an option providing “support to the wives of the recipients of the draft orders.”

The bulk of the conversation itself focuses on relaying reassuring messages. “As things currently stand, nothing is happening. All you have to do is not go to a police station. Apart from that, there are no ramifications,” says the anonymous person manning the hotline. “They send out draft orders to intimidate us because they have the legal right to do so. Have there been any arrests in practice? No.”

In a conversation with another hotline, we were offered detailed explanations and promised real help. According to the hotline worker, the punishment for desertion lasting less than two years is 30 days behind bars – and most people usually serve a lot less than that. “If that were to happen, the first thing to do is call our hotline and press the star button to get to the emergency desk that deals with arrests. There’s a lawyer there who can prove that the person in question was unaware of the draft order, that it never actually arrived, so there are extenuating circumstances.”

The hotline responder continued to detail cases in which deserters were arrested but quickly released, adding why, in his opinion, the State of Israel will never succeed in drafting the ultra-Orthodox. “When you owe the bank 1,000 shekels, it’s not pleasant. When you owe it 100,000 shekels, you’ve got a major problem. But when you owe the bank 2 million shekels, it’s not you who’s got the problem – it’s the bank. When the country is dealing with 100,000 deserters, there will be exemptions, because there’s no way to deal with so many people. Even if they wanted to, there aren’t enough prisons to put all of these people into.”

The quantity of hotlines advertising their services suggests that this is not an isolated phenomenon, but they are not the only explanation to the indifference and are, in fact, a mirror image of quiet efforts being made by some ultra-Orthodox communities to reach agreements with the IDF over a solution tailored to their specific needs. It is in the interests of both sides to keep these contacts well below the radar, but still some of them have been leaked to the media. There have been reports, for example, about the Karlin-Stolin and Belz Hasidic dynasties. “The Belzer rebbe is waiting to see what happens with the Karlin-Stolin; if they are successful, he might decide to join” says Shlomo, a Belz Hasid who is involved in the issue. “He is a lot more open-minded when it comes to the question of the draft. He is cautious, admittedly, but he’s not afraid to weigh the matter.”

What, then, are these possible alternative solutions? According to officials and functionaries from the ultra-Orthodox world, each community defines the appropriate solution based on its level of openness, the extent of its religiosity and other factors – but, in general, the options range from national service – to which the IDF is opposed – to service in the police or other emergency services. There is also the possibility of military service in various religious roles, similar to the model adopted for Chabadniks who opt to join the army.

Another tool used to “reassure” the potential draftee/deserter is rather indirect and comes, of all places, from the fringes of ultra-Orthodox society: yeshivas for dropouts, known as “summer camps,” where students who have dropped out of regular yeshivas are sent in an effort to keep them within the community. Many Haredim, various sources tell Shomrim, are convinced that if there is a mass draft of the ultra-Orthodox, it will mainly be these dropouts, who will fill the quotas set by the state. “Is your child in a good yeshiva and studying hard?” one of them explains. “If the answer is yes, he’s safe.”

The political and rabbinical leadership

The crisis of leadership among the ultra-Orthodox public also has an impact, but opinions differ as to what exactly that impact is.

In recent years, researchers explain, and for the first time in many decades, a leadership vacuum has emerged in the ultra-Orthodox world, in part because of the lack of rabbinical figures on whom there is a broad consensus and reverence that extends to every stream of ultra-Orthodox society. How does this feed the indifference? According to some, the lack of dominant figures has thus far made it hard for ultra-Orthodox politicians and officials to come up with common red lines and to launch a struggle in which several streams are engaged. For example, there are gaps in terms of willingness to compromise, the decision to bolt the government was taken by each ultra-Orthodox party separately and each of them still maintains some kind of contact with Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu and his coalition – with Shas serving as the most right-wing of them and the closest to the prime minister. Thus far, these gaps have prevented a sense of emergency from filtering down to the ultra-Orthodox street and the establishment of a joint struggle.

Another explanation describes a sense of helplessness created by the lack of a “spiritual guide” – a feeling that in turn leads to a sense of “There’s nothing I can do.” Shalom, an ultra-Orthodox man in his forties and the father of several children who are close to draft age, explains. “The inclination to rely on the leaders is built into our DNA as Haredim. Our leaders are responsible for everything and manage to fix everything. When an ultra-Orthodox person sees that the leadership is weak and there’s no one to fix things, they do not feel that they should step in to replace the rabbis. Instead, they say to themselves that it’s not their responsibility, that God will help and now it’s time for an afternoon nap.”

Rather surprisingly, these sentiments were clearly echoed in the random conversations Shomrim conducted on the streets of Bnei Brak, where people spoke nostalgically about the days of venerated leaders like Rabbi Shach and Rabbi Shteinman – and longing for a rabbi-led solution to their problems. Where are the ultra-Orthodox politicians in all this? “When you talk to people, it’s hard not to get the impression that they think their elected Knesset members are worth very little,” says Rabinovitz. “If, over the course of two and half years, they didn’t manage to resolve the draft issue, and New Horizon [the Ministry of Education reform, which was supposed to inject significant budget additions to ultra-Orthodox schools and teachers] isn’t happening, what are they doing in the government apart from feather their own nests and those of people close to them?”

Rabinovitz adds: “What’s a person supposed to do? Does he tell himself that he can change reality? No, he accepts that this is what there is.”