The Changing Face of the Golan: Record Number of Druze Requesting Israeli Citizenship

Fifty-five years after the Six-Day War, and more thana decade after the outbreak of the Syrian civil war, the Druze population onthe Israeli-occupied Golan Heights is torn between the two countries. A freedomof information request filed by Shomrim reveals a record number of requests forIsraeli citizenship – but these are often submitted in secret. Sometimes, evenfamily members don’t know. One young Druze woman who took Israeli citizenship: Ihave never felt any kind of affinity to Syria or Israel. I asked for citizenshipto make my life easier.

Fifty-five years after the Six-Day War, and more thana decade after the outbreak of the Syrian civil war, the Druze population onthe Israeli-occupied Golan Heights is torn between the two countries. A freedomof information request filed by Shomrim reveals a record number of requests forIsraeli citizenship – but these are often submitted in secret. Sometimes, evenfamily members don’t know. One young Druze woman who took Israeli citizenship: Ihave never felt any kind of affinity to Syria or Israel. I asked for citizenshipto make my life easier.

Fifty-five years after the Six-Day War, and more thana decade after the outbreak of the Syrian civil war, the Druze population onthe Israeli-occupied Golan Heights is torn between the two countries. A freedomof information request filed by Shomrim reveals a record number of requests forIsraeli citizenship – but these are often submitted in secret. Sometimes, evenfamily members don’t know. One young Druze woman who took Israeli citizenship: Ihave never felt any kind of affinity to Syria or Israel. I asked for citizenshipto make my life easier.

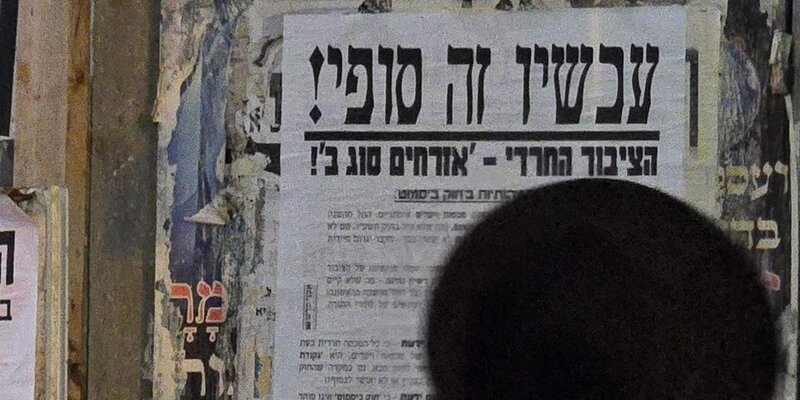

A member of the Druze community walks in front of Syrian flags during a rally in the Druze village of Majdal Shams on the Golan Heights. Photo: Reuters

Fadi Amun

September 4, 2022

Summary

Listen to a Dynamic Summary of the Article

Created using NotebookLM AI tool

F

or the past five decades or so, the Druze residents of the Golan Heights have jealously guarded the Syrian characteristics of their identity. Sharp-eyed visitors can see the signs on the alleyways of the villages and the faithfulness to a way of life that dates back to the time when the Golan was in Syrian hands – from working their lands, without external help, through maintaining commercial and academic ties with Damascus, to demonstrations in of support for the Syrian regime. Neither the improved economic situation of the Druze population nor the concerted efforts of successive Israeli governments to end that connection has made any difference.

In recent years, however, the picture has slowly started to change and, ironically, the change has created a common interest between the Druze community on the Golan and Israeli state institutions: Both would generally prefer there not to be an open public discussion about this process.

Either way, statistics obtained through a freedom of information request submitted by Shomrim through the Movement for Freedom of Information show that over the past five years, the number of citizenship requests filed by Druze residents of the Golan Heights jumped from between 75 and 85 requests a year in 2017 and 2018, to around 239 in 2021 – a number that will be exceeded this year, since 206 requests were approved in the first half of the year alone. Of the 21,000 Druze residents on the Golan, Interior Ministry figures show that some 4,300 are citizens of the State of Israel. Some of these are the children of Druze residents who have previously taken Israeli citizenship.

While writing this article, Shomrim contacted dozens of Druze residents of the Golan, asking for an interview. Among those Druze with strong affiliations to Israel, including those involved in local government and people who are actively involved in helping obtain Israeli citizenship, there was a blanket refusal to talk to Shomrim. Their main concern was that they would be subjected to pressure from their community were they to speak openly. At the time, interview requests were also turned down by people who opposed taking Israeli citizenship, who said that talking to the media could make them ‘targets’ for the Israeli authorities.

One of the few people who agreed to talk to Shomrim is M., a woman in her early 20s who grew up in a family that had never sought Israeli citizenship. She describes a community in which, over the past few years, a new, alternative narrative has become common – one that questions the loyalty of the Syrian regime to the Druze community on the Golan Heights and the difficulty that young Druze have identified with Syria, a country they have never even visited. “I have never felt any kind of affinity to Syria or to Israel,” she says. Her decision to request citizenship, which she kept secret from her extended family, was motivated by convenience alone since it would help her in her work and travel.

Abstaining From Local Elections

Ever since Israel captured the Golan Heights in the Six-Day War in 1967, the Druze residents have maintained a tight connection with Syria, which the Syrian regime has naturally encouraged. Commercial ties, for example, have been maintained, Druze residents of the Golan study for free in Syrian academic institutions, there have been family reunifications, marriages have been arranged between Druze on either side of the border, and so on. The Druze, for their part, have made sure that their loyalty to the Syrian regime is public by holding regular demonstrations and protests against Israel's control of the Heights. Many residents remember the six-month general strike in 1982, called to protest the passage of the Golan Heights Law, which applied Israel's government and laws to the territory. There have also been recent examples of protest, such as the removal of an Israeli flag in Majdal Shams and protests against holding local elections. Indeed, the extent to which local elections are seen as legitimizing the Israel regime can be seen in voting figures for Majdal Shams in the 2018 local election, when, out of a total population of around 12,000 people, just 272 voted.

A more violent protest occurred in 2015 when Druze on the Golan attacked an ambulance evacuating people wounded in the Syrian civil war for treatment in Israel – an act they interpreted as interfering in the conflict.

The process of naturalizing Druze residents of the Golan began shortly after the passage of the Golan Heights Law in the early 1980s, but there was only a small trickle of people taking citizenship. According to figures from the Population and Immigration Authority, just four Druze took Israeli citizenship in 2010. Over the subsequent three years, the number of naturalization cases varied from 14 to 18 a year, and during the next few years, when the Syrian civil war was raging, the number began to climb slowly, breaking records in 2016 and 2019.

In the past two years, there have been record numbers of citizenship requests, as the attached figures – which, as previously mentioned, were only made available following a freedom of information requestion – demonstrate. In 2021, during the first part of which it was still impossible to get an appointment with the Interior Ministry because of the coronavirus pandemic, a total of 239 citizenship requests were granted. In 2022, the number continued to climb, with 206 requests approved in the first six months of the year alone.

Ever since Israel captured the Golan Heights in the Six-Day War in 1967, the Druze residents have maintained a tight connection with Syria, which the Syrian regime has naturally encouraged. Commercial ties, for example, have been maintained, Druze residents of the Golan study for free in Syrian academic institutions, there have been family reunifications, marriages have been arranged between Druze on either side of the border

What sparked the change?

Dr. Yusri Hazran is a historian and senior lecturer at Shalem College in Jerusalem. His research analyzing the trends and changes in Druze society on the Golan Heights is due to be published in the coming months. He says he also encountered significant difficulties getting people to interview for his research. Based on data in his possession, he predicts that within some 20 years, around half of the Druze residents of the Golan Heights will hold Israeli citizenship.

“Over the past ten years, political protests against the State of Israel have dwindled,” he explains. “That’s in part due to the events in Syria. What happened there [the civil war] has smashed the idea of a Syrian nation, and that, of course, has practical implications for the Golan Heights. For example, there are almost no Druze students traveling to Syria to study, despite their far-reaching benefits, such as automatic acceptance to certain disciplines without taking an entry exam and exemption from tuition. The marketing of agricultural produce has also ended.”

Hazran believes that there is no “Israelization,” as he puts it, of the Golan Druze community. “The collapse of the Syrian state and the devastation there forced the Golan Druze to choose the rational option: integrate into the Israel sphere. It’s a practical integration. I can sum it up in four words: Recognizing reality, not Zionism.”

Among the reasons that Hazran cites for opposition to Israeli citizenship is the community’s concern for the fate of their families on the other side of the border – concerns that were exacerbated when, during the civil war, there were several attacks on Druze villages inside Syria by rebel forces.

“The number of people taking Israeli citizenship may be high, but, to my understanding, there is no inherent change in the community’s worldview. A survey I conducted as part of my research asked questions about self-identification; most of the respondents identified themselves as Syrian Druze or Arab Druze. Despite the huge crisis in Syria, they adhere to their Syrian national identity. For them, taking Israeli citizenship is not Israelization or Zionization but a rational choice that they hope will improve their quality of life. This approach also characterizes Arab society in the rest of Israel and some of the Muslim population of Jerusalem.”

Dr. Hazran believes that there is no “Israelization,” as he puts it, of the Golan Druze community. “The collapse of the Syrian state and the devastation there forced the Golan Druze to choose the rational option: integrate into the Israel sphere. It’s a practical integration. I can sum it up in four words: Recognizing reality, not Zionism.”

An Alternative Narrative to Israeli Rule

M., the Druze woman in her early 20s, applied for Israeli citizenship in 2021 and was granted it quickly. “My parents don’t have [Israeli] citizenship, and they accepted and respected my decision. The broader family doesn’t know about it, and I assume that if they were to find out, some of my relatives would sever their ties with me.”

M. says she completely understands the widespread opposition to taking Israeli citizenship, especially from older people who “experienced first-hand a bloody war.” She adds that, in recent years, an alternative narrative to the Six-Day War emerged in villages on the Golan Heights, which does not contribute to residents’ sense of identification with the Syrian regime. “Some people say Israel did not really capture the Golan Heights, but the Syrian regime sold us out. Others say that Israel captured the Heights and, in so doing, carried out mass murders and expelled many Druze from their homes. Many people don’t know the history and have no idea what the truth is.”

She herself was born more than 30 years after the Six-Day War, and “I don’t know anything else apart from Israel.” She says that her dream is to study medicine in Damascus, but the civil war has made that impossible. Instead, she studied at an academic institution in Israel, and since graduating, she has worked for several Israeli companies. She has also found time to travel overseas with her family. Not having citizenship, she says, made life hard for her every step of the way, especially when traveling between countries, so she decided to request Israeli citizenship and improve her quality of life.

Political Citizenship and Protest: Druze Voting Likud

The results of the last Knesset election, held in March 201, amply illustrate the range of dilemmas facing the Druze community on the Golan Heights, but with a surprising twist: Likud is the big winner of the Druze vote.

In Majdal Shams, the largest Druze town, there are some 2,068 Israeli citizens, some of whom are minors. In the last election for the Knesset, there were 962 eligible voters living in the town, of whom just 169 exercised their right to vote – that’s 17.5 percent of the eligible voters, while the turnout for the whole of Israel was 67 percent. This is a low figure even compared to Arab communities inside Israel, where the average voter turnout was 44 percent. The turnout was similar in other Druze communities, with 19 percent in Mas'ade, 15 percent in Buq’ata, and 10 percent in Ein Qiniyye.

Several explanations for this low voter turnout include lack of identification with the State of Israel, fear of being exposed as Israeli citizens, and indifference toward the Israeli regime. All of these explanations fit in with Yusri Hazran’s analysis. Similar patterns can be seen in municipal elections in Jerusalem, where the Palestinian population that holds Jerusalem residency permits opts not to vote.

However, the narrative takes an interesting twist when looking at the election results. The right-wing won most votes from Druze on the Golan Heights, with Likud being the preferred party by a large margin. In Majdal Shams, for example, the party led by Benjamin Netanyahu won 65 of the 169 votes cast and was also the largest party in Mas'ade and Ein Qiniyye.

In Buq’ata, Avigdor Lieberman’s Yisrael Beiteinu party, which identifies as the party for immigrants from the former Soviet Union, was the largest.