‘Getting Married Was the Worst Decision of My Life’: Arab Society is Worried by the Rising Divorce Rate

Teenage marriages, family pressure, a patriarchal establishment and exposure to a liberal lifestyle are just some of the reasons for a steady climb in the divorce rate among Israel’s Arabs. This year, more than 4,000 couples have divorced – part of an upward trend that has been going on for years. Alongside the social problems, efforts are being made to deal with the phenomenon. A Shomrim report

Teenage marriages, family pressure, a patriarchal establishment and exposure to a liberal lifestyle are just some of the reasons for a steady climb in the divorce rate among Israel’s Arabs. This year, more than 4,000 couples have divorced – part of an upward trend that has been going on for years. Alongside the social problems, efforts are being made to deal with the phenomenon. A Shomrim report

Teenage marriages, family pressure, a patriarchal establishment and exposure to a liberal lifestyle are just some of the reasons for a steady climb in the divorce rate among Israel’s Arabs. This year, more than 4,000 couples have divorced – part of an upward trend that has been going on for years. Alongside the social problems, efforts are being made to deal with the phenomenon. A Shomrim report

Photo illustration: Shutterstock

Fadi Amun

July 15, 2025

Summary

Listen to a Dynamic Summary of the Article

Created using NotebookLM AI tool

Yasmin, a 24-year-old woman from the Arab town of Jadeidi-Makr, tells Shomrim that she got married at the age of 18. “I didn’t even have time to go to university,” she says. The marriage did not last and the couple divorced four years ago. “My parents pressured me to get married because they wanted grandchildren. My ex-husband isn’t a lot older than me; he was 22 when we got married. He worked as a truck driver and earned a meager livelihood; I didn’t work because he didn’t want me to. In conservative families, they prefer that the woman doesn’t have a job. We fought a lot, partly because I was stuck at home the whole time and partly because I didn’t even know him before the wedding.”

Yasmin’s story is far from unusual. Despite the tendency of the Muslim Arab population in Israel toward conservatism – especially in matters relating to the family – divorce has become a relatively common phenomenon, with a steady rise in the number of married couples splitting up. There has been a sharp increase in both the number of new divorce cases opened each year and in the number of cases that are finalized and the couple is officially no longer married. The most dramatic figure comes from mixed Jewish-Arab towns where, according to various indices, around 50 percent of all marriages are likely to end in divorce.

When comparing the figures to the number of couples registering to wed, the change is especially stark. “In Jaffa, the figure is very close to 50 percent and in Acre and Haifa, around 45 percent of all couples divorce,” says Dr. Iyad Zahalka, the head of the Sharia Courts. “In the rest of the Arab cities and communities, the divorce rate is between 20 and 30 percent.”

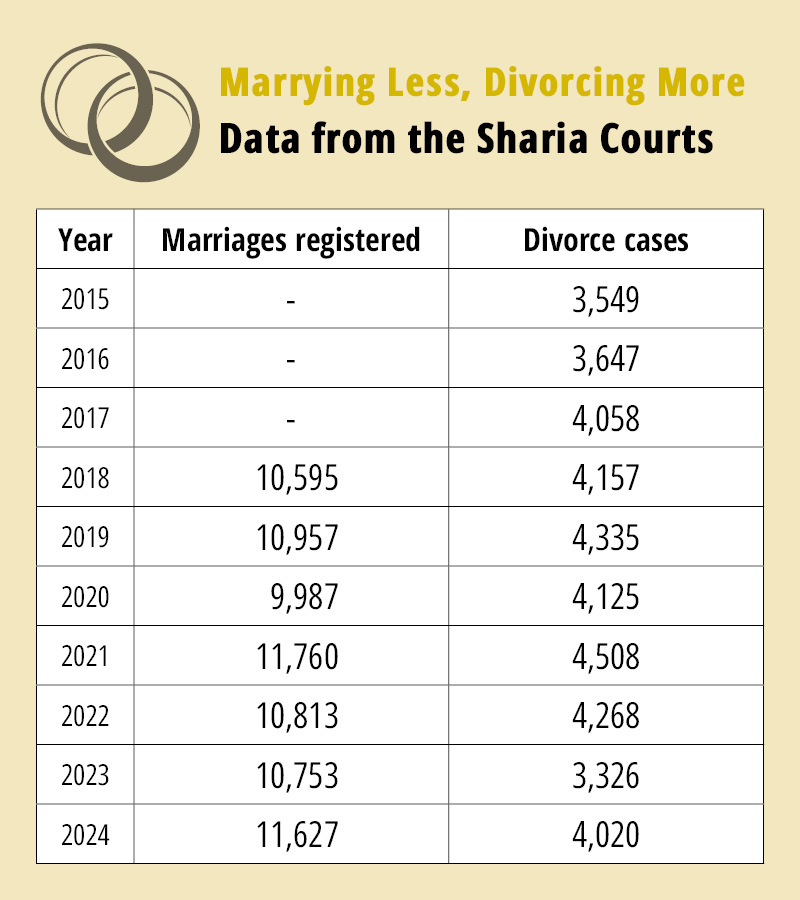

According to data from the Sharia Courts, the number of divorce proceedings initiated rose steadily from 3,549 cases per year in 2015 to 4,268 in 2022. In 2023, there was a decline to 3,326 cases, but the figure rose again in 2024, reaching 4,020. According to Zahalka, the decrease in 2023 was due to a regulatory amendment requiring couples to attend mediation before filing for divorce — a change that had a significant impact on the numbers.

“Our goal is to encourage couples who are experiencing difficulties to try and work them out using professional counsellors from the welfare units attached to the court. Social workers, lawyers and psychologists – all with mediation training – and an effort to help families going through a process of separation,” Zahalka says. “When there are more divorced families, society is more fragmented. We see that children of divorced parents suffer more from behavioral problems., To a certain extent, you can say that the rise in criminality in Arab society is linked to the divorce rate.”

‘My life was ruined’

“Getting married at the age of 22 was the worst mistake I ever made. Even though we didn’t have children, my life was ruined,” Faud, a resident of Taibeh, tells Shomrim. He and his wife divorced after around 18 months of marriage. “I wasn’t mature enough and neither was my ex-wife. I’m 27 now and I didn’t get remarried. I’m not even thinking about it. A lot of people in Arab society think that it’s important and even compulsory to get married young – but that’s a mistake.”

Zahalka, who sees many young people like Faud and Yasmin in the offices of the Sharia Court, agrees that getting married too young and without the necessary emotional maturity, leads to more confrontations and, as a result of that, to more divorces. “Couples have to make use of their engagement period to get to know each other and to see whether they are compatible. We need to increase their awareness about what happens after the wedding. If we, the qadis at the Sharia Courts, manage to mediate conflicts that stem from lack of familiarity with each other, we can bring the divorce rate down.”

Divorce in the Arab sector can also sometimes be due to factors other than age, of course. Some of the people interviewed for this article mention the clan-based structure of Arab society, its heavily patriarchal and traditional nature, or the fact that the new couple’s home is often built very close to the husband’s extended family, which is not always best for a newlywed couple.

“After the wedding, his family – and mine – started pressuring me to get pregnant,” Yasmin recalls. “That led to a lot of tensions and fights with the parents. When we tried to get pregnant, it turned out he has a medical problem. He refused to accept that and so did his parents. He said it was my fault. It’s a good job we did not have children, otherwise the whole thing would have been a lot more complicated. I moved back in with my parents, began a new chapter in my life and I started to study at university.”

Prof. Sarah Abu-Kaf, an Associate Professor of Conflict Management and Resolution Program at Ben-Gurion University, explains that, in Arab society, the connection between the nuclear family and the extended family is usually very close. She notes that against this backdrop, two additional and complex levels of impact from the dissolution of the family unit – the impact on children and the economic aspect – are only intensifying.

“Divorce creates significant emotional distress for both parents and children. At the same time, there is also the economic aspect. In Arab society, in most divorce cases, the children remain in the mother’s custody. She, in turn, experiences a significant drop in her lifestyle, which means that in many cases, divorced Arab women are forced to work longer hours and have less free time to spend with their children,” she says.

Zahalka says that there is another reason for the climbing divorce rate among Israeli Arabs, especially in mixed communities: exposure to a liberal lifestyle, which sanctifies individualism. “This change has been swift and sharp. Many people adopt these ideas, which are different from what they are used to, without understanding the impact it could have on their lives. It leads to many problems, of which divorce is just one. If, in the past, individuals tried very hard to please the society from which they come, today things are different. They care about their careers, business, private life – and that comes at the expense of other things, including the family.”

Zahalka believes that these processes are happening without any direct connection to the status of the family in Arab society, but they are putting the institution of marriage under pressure. “The individual no longer takes others into account. His ‘self’ has moved to a higher place on the scale and this causes him to have less desire to reconcile in order to preserve the family unit.”

More education means more financial independence

Dr. Maha Sabbah-Karkabi, a senior lecturer at Ben-Gurion’s Department of Sociology and Anthropology, says that the main reasons behind the increased divorce rate are social and economic. “The most significant change is the rise in the average level of education, which is especially felt among the female population. The more education they get, the more financial independence they enjoy. The increased number of women joining the workforce also means a drop in the number of children and it also has an impact on the choice of partner, the climb in the average age that Arab women are getting married and in the divorce rate. It’s all connected,” she explains.

Part of the economic aspect is also the perception of the husband as the primary earner. “In the past, there was a very clear division between the role of the husband and that of the wife. Women were dependent on men and many lived in a violent atmosphere – but had no choice but to remain in the circle of violence.”

“In the past, there were more unwritten rules. The community and the extended family did not accept divorce. They condemned the very phenomenon, sometimes even going so far as to completely ostracize the divorcee,” Sabbah-Karkabi adds. “Today, society is a lot more accepting than it was in the past. The more the phenomenon becomes widespread, the less it is seen as a deviation from the societal norm. Today, there is also more flexibility than in the past, the result of liberal values seeping into Arab society.”

“Society accepts that individuals have the right to be happy with their relationships and, if they are not, they have the right to end that connection,” she says, noting another important phenomenon in this context: “My studies have shown that the trends of change that I described are different in different sectors of Arab society – like class, for example, which is the subject of my current study.”

“Today, women are economic units who are capable of managing themselves,” says Jihan Abdalhaq, an attorney whose work includes family law. “If a woman is not getting along with her husband, the pressure that used to exist is no longer there – that the man is supposed to support her and she should stand down. Women know that they can make a living without a man; that they can study or work without a husband. Most Arab women now have a profession and qualifications.”

In addition to the “economic shift” as a catalyst to a higher divorce rate, Abdalhaq would also add two factors that have already been mentioned: the first is the involvement of the extended families in the couple’s relationship; and the second is tension over children. These issues are openly brought up time and time again in various forums which deal with divorce, but there is still no systemic solution to help couples deal with the challenges they create. One outlier in this respect is a seminar for Druze couples who are about to get married or for those married less than two years. The seven-meeting course is divided into three sections covering religion, home economics and parenthood. In the meantime, there have only been two such classes – in Abu Snan and Beit Jann, with a total of 30 couples participating. According to an official from the Druze Religious Council, the goal of the program is to reduce the high divorce rate in the community, given that studies have shown that most Druze divorces happen within the first five years of marriage.